Jake Yankee- Natural Resources Conservation

Olivia Babine- Environmental Science

Ben D’Ambra- Horticultural Science

Kayshauna Montano- Animal Science

The North Atlantic right whale, Eubalaena glacialis, faces a number of challenges to its recovery. Their habitat includes the waters off the U.S. East coast where they come into contact with pollutants, fishing gear, and boats that threaten their survival. The greatest source of right whale mortality is collisions with vessels. In order to mitigate this problem, researchers have utilized a number of strategies to help vessels and whales occupy the same space without colliding with one another. One of the most popular strategies is vessel speed restriction zones. These are geographic areas in the ocean designated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration where vessels must slow down to accommodate right whales (Mullen 2013). While these zones cover much of the right whale’s current range, their distribution is patchy with long stretches of unprotected space between them and they do not extend far enough offshore to cover the whale’s entire habitat. To increase the effectiveness of these zones and better protect right whales from ship strikes, we propose that protection areas be expanded to cover the entire U.S. East coast and to extend 30 nautical miles offshore.

The North Atlantic Right Whale is critically endangered and has been listed under the Endangered Species Act since 1970. According to recent estimates, the population of right whales has significantly dropped within the last year, from 450 to around 400 (Bragg. 2018). According to Bragg, to sustain the critically endangered population along the U.S. and Canadian coast, there should be no more than one right whale death per year (Bragg. 2018). So far in 2018 there has already been 3 documented right whale deaths in U.S. waters. According to an article published by Mike Gaworecki, new research suggests that human activities are negatively impacting the population growth of North Atlantic right whales. The article also stated that there’s believed to be only 100 females left in the right whale population (Gaworecki. 2018). Based on a study conducted by Peter Corkeron, who is head of whale research at NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service, after comparing calf counts from 1992 to 2016 of four populations of right whales, Corkeron and his co-authors found that the annual rate of increase of North Atlantic right whales was only about 2 percent per year (Gaworecki. 2018). This slow rate of only 2 percent per year is significantly lower than other right whale populations that were studied. Other right whales increased their population by anywhere from 5-7.2 percent.

Ship strikes threaten survival of the critically endangered North Atlantic Right Whale. The right whale’s behavior is partly to blame for why they get struck by vessels so frequently. They do not respond to the sound of an approaching vessel and or turn away when they are about to collide (Vanderlaan & Taggart 2007). Consequently, ship strikes are the single greatest cause of right whale mortality. A study by Knowlton and Kraus (2001) found that 35.5% of the 45 documented right whale mortalities between 1970 and 1999 were caused by ship strikes. This was more than any other cause of death. Another study by Laist et al. (2014) looked at all of the right whale mortalities between 1990 and 2012, and found that 23 out of the 79 deaths, or about 29%, were due to ship strikes. These percentages indicate that ship strike is a serious threat to the right whale population.

Ship strikes are the number one cause of right whale mortality

The NOAA Fisheries website on the North Atlantic right whale states that they migrate seasonally and either travel alone or in small groups. They are found in their northern habitats, where they feed and mate in all seasons except the winter. During winter, pregnant females give birth in the only known calving area off the southeastern United States (NOAA, 2018). North Atlantic right whales live in Atlantic coastal waters and most nurseries are located in shallow, coastal waters. Each year during the fall, some right whales travel from Canadian and New England waters down to warm southern coastal waters, near South Carolina and Georgia to give birth and nurse the young right whale calves (NOAA. 2018). The website also states that the migratory and habitat patterns overlap with shipping ports in the Atlantic seaboard. Having this overlap in major shipping ports and right whale migration routes causes the whales to sustain vessel ship strike related injuries, sometimes resulting in death.

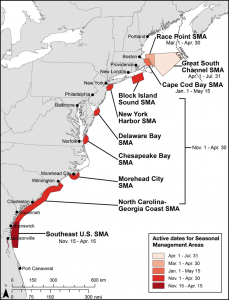

Our proposal to enhance protection for North Atlantic right whales from ship strikes is to expand Seasonal Management Areas for right whales. Seasonal Management Areas (SMAs) are designated areas in the ocean that become active at certain times of the year when right whales are known to occupy them (Mullen, Peterson, & Todd 2013). There are currently 10 SMAs for right whales that extent from the northern coast of Florida to the waters directly east of Cape Cod, including areas of migration and feeding. They were implemented in 2008 to cover major ports where boat traffic is high. All of the SMAs extend 20 nautical miles offshore and are active from November 1 to April 30 every year. Vessel speed reduction in these areas is mandatory, at 10 knots or less for vessels larger than 65 feet (NOAA, 2012.) Compliance with this policy was initially poor, but has increased over the years (Laist, Knowlton, and Pendleton 2014).

Seasonal Management Areas for right whales along the U.S. Atlantic coast.

We are proposing an expansion to SMAs because they are an effective strategy for reducing ship strike mortalities in right whales. According to the study conducted by Laist, Knowlton, and Pendleton (2014), the average annual discovery rate of ship struck whale carcasses in or near SMAs declined from 0.72 per year in the 18 years prior to their implementation to 0 carcasses per year in the first five years after SMAs were implemented. Their research concluded that the majority of right whale deaths prior to the implemented rule in 2008 were found in or within 6 nautical miles of SMA’s, suggesting that SMAs do work in reducing ship strike whale mortalities (Laist, Knowlton, & Pendleton 2014). When ships reduce their speed in SMAs, they decrease the chances of killing a right whale in a collision. The chances of lethal injury to a whale, being defined as death or severe injury, are 80% at 15 knots. At 8.6 knots, the chance of lethal injury decreases 20%. The chances approach 100% at speeds above 15 knots, and dip below 50% at 11.8 knots. Considering that the average vessel speed in two critical right whale habitat areas have been found to be 14-16 knots, the 10 knot speed restriction in SMAs is an effective way to reduce whale mortalities (Vanderlaan & Taggart 2007).

While SMAs are effective, they do not reach their fullest potential for protecting right whales. One of the greatest flaws in SMAs is their patchy distribution and relatively limited coverage. There are large tracts of unprotected waters between each SMA, especially in the mid-Atlantic region of the right whale’s range. The area originally known to be as the full migratory track of right whales extends 30 nautical miles offshore, whereas protection zones extend just 20 nautical miles offshore. The exclusion of these 10 nautical miles leaves room for more vessel collisions (Laist, Knowlton, & Pendleton 2014). This is especially problematic because the highest number of ship strike mortalities occur in this region (Mullen, Peterson, & Todd 2013). A significant amount of right whale carcasses discovered before the 2008 rule, categorized as ship strike deaths, were found moderately decomposed meaning the whale had been deceased for up to several weeks. During this time, it is common for the whale carcass to drift up even up to 45 nautical miles, so there is high possibility that the initial ship strike occurred far outside of SMA boundaries, placing greater importance on modifying these established areas (Laist, Knowlton, & Pendleton 2014.) The extent of SMAs should be expanded to connect the current SMAs along the U.S. Atlantic coast to protect right whales as much as possible.

While shown to be effective at protecting the north atlantic right whale species, some have found mandatory speed restrictions to negatively impact safety regarding ship navigation, as well as economically, from the perspective of commercial shipping industries. The American Pilots’ Association voiced their concern for the safety of maneuvering vessels through these protected zones, claiming lowered speeds could increase the chance of vessel accidents, resulting in human casualties as well as marine life casualties (American Pilots’ Association 2008.) Several studies have examined Mariner’s perspectives on speed restriction zones in SMA’s. A report released by NOAA examines the negative economic impact that speed restrictions have on the shipping industry. Shipping industries report that delays in arrivals to ports in a trip alter their ability to stay on schedule, can cause missed tidal windows, and can ultimately increase overall costs to the industry due to hired but unused labor at scheduled ports within their route (NOAA, 2012.)

To ensure that safety of human beings is not in question regarding speed reductions within SMAs, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association offers an easily accessible compliance guide for mariners. If traveling at 10 knots or less within these areas bring safety in to question while maneuvering vessels, the 10 knot limit can be exceeded so long as this information is properly logged, and signed by the operator of the vessel (NOAA 2012.) In terms of economic costs, shipping industries have found that traveling to less ports per trip can help in staying on schedule, and avoids having to add additional vessels to ensure weekly service. NOAA’s analysis on 2009 containership trips suggests that speed restrictions do not negatively impact every vessel traveling to several ports, and those that are impacted usually have an average delay of only 11 minutes, making missed tidal windows rare (NOAA, 2012.)

Adding on to opposing views of speed restrictions, the United States government has played a big role in reducing the advancement of speed restriction zones. (https://www.ucsusa.org/) Starting in 2004, the National Marine Fisheries Services (NMFS) drafted a rule based on research from the organization’s scientists to enforce speed restriction zones for right whale protection (https://www.ucsusa.org/). They found that whale casualties due to collision increased when speed was increased from 10 knots to 14 knots (https://www.ucsusa.org/). The rule was then published in February 2007, and was thoroughly debated by the White House Council of Economic Advisors (CEA) (https://www.ucsusa.org/). The CEA collected data from other scientists in the United States and from Canada and ran a sensitivity analysis using the new data and the data of the NMFS in which they changed the coding in data points by changing the outcome of the whale involved in collisions from being “serious” to “not serious,” causing biased results (https://www.ucsusa.org/). The CEA argued that the NMFS data was only based on a few points, and therefore, did not have enough evidence to support the true efficacy of reducing speed (https://www.ucsusa.org/). The rule was eventually passed, with a few alterations that included reducing the size of protection zones from 30 miles to 20 miles, making speed restrictions optional instead of obligatory, and had a 5 year clause that stated the NMFS had to re-do data to attempt to remake the rule (https://www.ucsusa.org/).

The American whaling industry nearly drove the North Atlantic right whale to extinction.

Human interaction with the North Atlantic right whale has, since the peak of the whaling era, been the predominant cause of their survival as a species. In today’s time, collisions between individual whales and ships have been shown to be the leading cause of death within these species due to the immediate trauma and damage caused by the strike (Knowlton & Kraus 2001.) Protective measures put into place to decrease likelihood of right whale deaths, such as SMA’s and speed restrictions, have shown to be effective at reducing mortality, however with a global population of close to 400 individuals, even few deaths per year can heavily impact the recovery of the species. Several studies have examined the ability of speed restrictions within SMA’s to assist in reducing right whale deaths, and conclude their effectiveness, yet also recommend that protected areas must be increased. Expanding SMA’s and speed restrictions to areas further offshore, covering more of the migratory track of this species could reduce whale and ship collisions even further (Laist, Knowlton & Pendleton 2014.)

References

American Pilots Association. (2008). “Comments of the American Pilots’ Association On the

Final Environmental Impact Statement on Ship Strike Reduction Measures.” Retrieved from http://www.americanpilots.org/document_center/Activities/Comments_on_Final_EIS_for_Right_Whale_Rule_9_29_08.pdf

Bragg, Mary Ann. “New Estimate Lowers Number of Right Whales.” The Inquirer and Mirror,

The Inquirer and Mirror, 8 Nov. 2018,

www.ack.net/news/20181108/new-estimate-lowers-number-of-right-whales.

Freedman, R., Herron, S., Byrd, M., Birney, K., Morten, J., Shafritz, B., Caldow, C., Hastings,

S.. (2017). The effectiveness of incentivized and non-incentivized vessel speed reduction

programs: Case study in the Santa Barbara channel. Ocean & Coastal Management, 148,

31-39. Doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2017.07.013.

Gaworecki, Mike. “Human Activities Are Impeding Population Growth of North Atlantic Right

Whales.” Conservation News, Conservation News, 19 Nov. 2018, news.mongabay.com/2018/11/human-activities-are-impeding-population-growth-of-north-atlantic-right-whales/.

Knowlton, A. R., & Kraus, S. D. (2001). Mortality and serious injury of northern right whales

(Eubalaena glacialis) in the western North Atlantic Ocean. J. Cetacean Res. Manage (2) 193-208. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.557.7497&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Laist, D., Knowlton, A., & Pendleton, D. (2014). Effectiveness of mandatory vessel speed limits

for protecting North Atlantic right whales. Endangered Species Research, 23(2), 133-147.

doi:10.3354/esr00586

Massport. (n.d.) Economic impact of the port of Boston. Lancaster, PA: Martin Associates.

Mullen, Kaitlyn A., Peterson, Michael L., Todd, Sean K. (2013). Has designating and protecting

critical habitat had an impact on endangered North Atlantic right whale ship strike

mortality?. Marine Policy, 42, 293-304. doi:

National Marine Fisheries Service (2008) Compliance Guide for Right Whale Ship Strike

Reduction Rule.

https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/national/endangered-species-conservation/reducing-ship-

Strikes-north-atlantic-right-whales

Silber, G. K. & Bettridge, S. (2012). An assessment of the final rule to implement vessel speed restrictions to reduce the threat of vessel collisions with North Atlantic right whales. Silver Spring, MD: National Marine Fisheries Service.

Vanderlaan, Angelina S. M., Taggart, Christopher T. (2007). Vessel collisions with whales: the

probability of lethal injury based on vessel speed. Marine Mammal Science, 23, 144-156.

doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2006.00098.x

great post. call 8967686952

Get in touch with us now for all your dating needs with Pune Dating Girls

Nice Article

Great Post Thanks For Sharing With Us

Nice Post

Great Post

Nice Post

Online İngilizce öğren. İngilizce video dersleriyle yeni kelimeler öğren, pratik çalışmaları ile İngilizce konuşmanı çok hızlı geliştir.

Best Digital Marketing Course Institute In Faridabad | SEO | SMO

Best Country to Study MBBS for in Indian Students