Angeline Palmer, of Amherst

By Cliff McCarthy

A version of this story appears on the website Freedom Stories of the Pioneer Valley and is used with permission.

Angeline Palmer was a freeborn African American raised in the Amherst alms-house.[1] Her mother died of smallpox in 1831 when Angeline was about two years old and her father, Solomon Palmer, does not appear in town records after 1834.[2] Angeline was considered a ward of the town and, as was customary in those days, the Amherst selectmen hired out Angeline as a servant to defray the cost to the town. She was “bound out” to Mason and Susanna (Dwight) Shaw of Belchertown, Massachusetts.[3]

The Shaws occupied a fine, Federal-style house on the Belchertown common (now 32 Park Street) which was built in about 1822 with landscape wallpaper and rare plants and trees on the grounds. Squire Shaw, as he was known, was an esteemed attorney in town.[4]

Although Mason Shaw was born in Raynham, Massachusetts, he had been living in Castine, Maine (which was part of Massachusetts until 1820), where he was clerk and sheriff of Hancock County. His first wife died in 1811 and several of their children died young.[5] In 1812, he married Susanna Dwight of Belchertown and she moved to Castine, where they had three more children, one of whom died young.[6] In the 1820 census, the family was listed in Maine, but they moved to Belchertown in 1821 and Squire Shaw took up agricultural pursuits.[7] Specifically, Mason Shaw got caught up in raising and selling mulberry trees for silkworms.

In 1829, Miss Waitstill D. Shaw, Mason’s daughter by his first wife, married in Belchertown, to Mr. Charles Cheney, of Providence, R.I. Originally from Connecticut, Charles Cheney was one of several brothers who began growing mulberry trees and cultivating silkworms to produce silk. Charles and Waitstill moved to the Cincinnati, Ohio area where he founded the Mulberry Grove Silk Growing and Manufacturing Company. The Cheney Brothers were among the premier silk manufacturers in the U.S. And so it was through the Cheney Brothers that Mason Shaw became involved in the silkworm/mulberry tree craze that swept over western Massachusetts at that time.[8] Many people, some in Belchertown, lost small fortunes when this industry collapsed.

About the time their daughter Susan married Calvin Bridgman in 1838,[9] Squire and Mrs. Shaw moved out of state, leaving their home in the care of Susan and her new husband. They left Angeline behind, as well, to serve the newlyweds. Mason Shaw moved to Augusta, Georgia in order to sell mulberry trees.[10]

In 1840, Susanna Shaw returned to Belchertown to visit. At some point during her stay, she received a letter from her husband which included the outlines of a scheme to bring the ten-year-old Angeline into Georgia where she could be sold as a slave.[11] Squire Shaw figured he could get about $600 for her. Although Massachusetts laws protected the freedom of all its residents, the laws of Georgia did not allow free Black people to live within the state, without legislative sanction.[12]

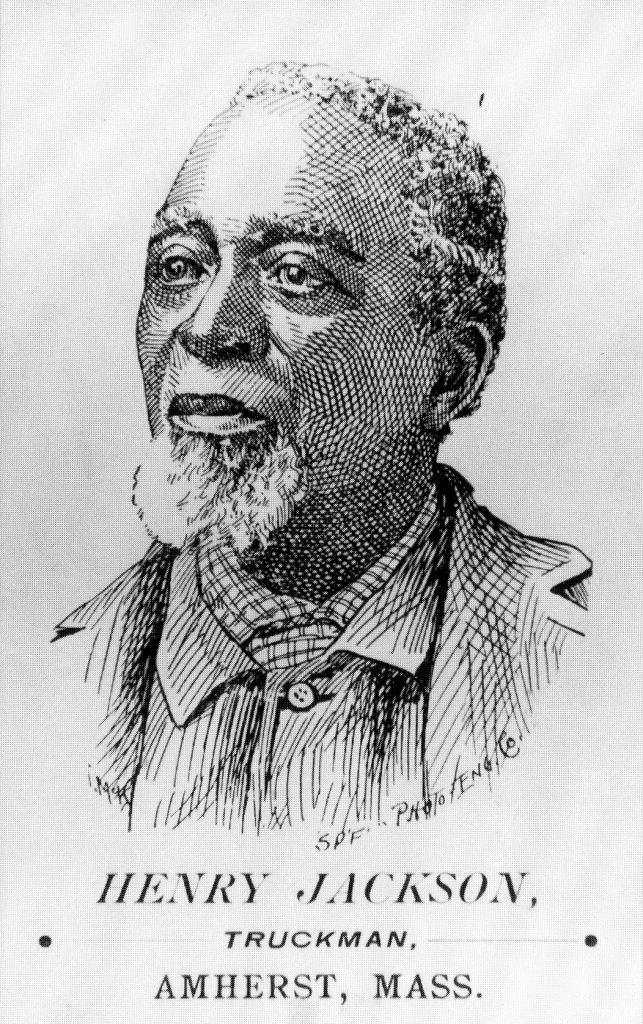

Servants in the house overheard the letter being read aloud and immediately raised the alarm with the African American community in Amherst. The Amherst selectmen were still legal guardians of the girl. Angeline Palmer’s half-brother was twenty-year-old Lewis Frazier and he and his friends Henry Jackson, 23, and William Jennings, 27, appealed to the selectmen to take action. The selectmen refused to get involved, leaving few options available.[13]

On May 26, the Shaws were preparing to depart from Belchertown on the following day. Angeline was in Amherst that day, saying goodbye to her grandmother who was a servant in the home of Hezekiah Wright Strong, the Amherst postmaster and Susanna Shaw’s brother-in-law. The grandmother learned that Frazier was planning to take action and told her employer that something was up. Afraid of outside interference, Strong hired a liveryman, Henry Frink, to deliver Angeline to the Shaws by private carriage, instead of sending her to Belchertown on the regular stagecoach.[14]

Strong’s intelligence proved correct, as Lewis Frazier and William Jennings did flag down the stage on its way to Belchertown, but not finding Angeline on board, they walked back to Amherst. Once there, they learned that Frink had taken Angeline to Belchertown by a different route.[15]

Courtesy of the Wood Museum of Springfield History

Frink, who was Henry Jackson’s employer, may have left word about his trip to Belchertown. He was later accused of helping Frazier and Jennings by taking “a circuitous route” to Belchertown via South East Street and Bay Road to allow time for the young men to act. However, Frink — who was also a deputy sheriff — claimed that Hezekiah Strong asked him to go that way instead of using the same route as the stagecoach.[16]

Once alerted, Frazier, Jackson, and Jennings sped to Belchertown in a horse and buggy they borrowed from a sympathetic white butcher. Frink had already delivered his passenger and retreated to a nearby pub by the time they arrived on Belchertown common.[17]

Frazier entered the Park Street home in search of his sister, while Jackson and Jennings waited in the wagon. A commotion erupted in the house, where Mrs. Shaw and a neighbor had Frazier – with Angeline in his arms – trapped in an upstairs room. Responding to their friend’s call for assistance, Jackson and Jennings forced their way into the house and up the stairs. They pushed Mrs. Shaw aside and opened the door and the three men led Angeline down the stairs, past a crowd that was assembling, and into the buggy.[18]

They raced back to Amherst. However, their hurried trip was interrupted when they sped past a rider going in the same direction towards Amherst. That rider, Sheriff Dwight, ordered them to stop. Dwight recognized Henry Jackson as one of his deputy’s loyal employees and, unaware of the abduction, warned the men about traveling at excessive speed, then sent them on their way. Angeline was hustled into the North Amherst home of Spencer Church, a white farmer and abolitionist. The next day, she was secretly transported to Colrain to the home of a black resident, Charles Green.[19]

Frazier, Jackson, Jennings and Frink were all arrested for assault and kidnapping and they all were free on bail until their trial in 1841. Their defense attorney was a young lawyer named Edward Dickinson, whose own daughter — the future poet, Emily Dickinson — was only a year younger than Angeline Palmer.[20]

At the trial, Frink, the only white defendant, was acquitted. The other three men were convicted, but offered their freedom if they would divulge the whereabouts of Angeline Palmer. All three refused and were sentenced to three months in the county jail.[21]

The newspapers were not pleased with the verdict. The Daily Hampshire Gazette opined: “The people of Amherst believe, pretty generally, that the fears of the blacks were justly excited about the little girl, and that Frazier was justified in rescuing her in the eye of humanity, if not in the eye of the statute law.”[22] Another newspaper, the Northampton Courier, lamented: “Had the selectmen of Amherst interfered and, as was their right, not to say their duty, forbidden the removal of the girl from the Commonwealth, all this trouble and expense might have been saved.”[23]

The prisoners themselves did something less than “hard time.” The jailer agreed to give them liberty each day on the promise that they would return to jail each evening. Local townsfolk provided gifts of good food for the men to supplement their usual jail fare. They were hailed as heroes in Amherst, upon their release.[24]

With the passage of time, the events of Angeline Palmer’s rescue receded into the past. She had returned to Amherst by 1851 when she wed Sanford C. Jackson, the brother of Henry Jackson’s wife (who was also a Jackson).[25] Angeline apparently died within a few years of her marriage, though no record of her death is known. Before she died, Angeline bore a son, named Richard Lewis Jackson, born on 19 August 1852.[26] It is quite possible that Angeline died in childbirth. Richard Lewis Jackson was noted in Amherst in the Massachusetts state census of 1855 in the care of a distant relative.[27] Sadly, the only other known evidence of her son’s life is that he was a resident of the almshouse in Brimfield in 1857. He may have been the Richard Jackson who died as a boy in the Monson almshouse of scarlet fever in 1858.[28]

Sanford Jackson provides an interesting footnote to the story, however. After Angeline’s death, he married a second time in 1859 to Emily Jane Mason in Wilbraham. A year later in Worcester, he apparently married a third time to Nancy Newport. Sanford Jackson enlisted in the Union Army in March of 1863, joining the famous 54th Massachusetts Volunteers. In July, he was wounded in South Carolina during the siege of Fort Wagner and died from his wounds two months later. After his death, both his wives, Emily and Nancy, applied separately for his widow’s pension.[29]

Local historian Robert Romer has researched this part of the story and has found that indeed two different “widows” — Emily Jane Mason and Nancy A. Newport — applied for Jackson’s benefits.[30] Emily applied for benefits in 1866, referring to her marriage to Sanford in 1859. Almost immediately, Sanford’s mother, Polly Jackson, stepped in and pointed out that Emily had married Charles Finnemore in 1854 and that Charles was still living in 1859 and that there was no record of a divorce. Therefore, Emily’s marriage to Sanford Jackson was not valid.

Emily may have been acting in good faith. She wrote that she had been told that Charles had died in prison. Charles did serve a 4-year term in the Charlestown prison and was discharged in 1860. He was also listed in the 1850 federal census as then residing in prison on a charge of larceny. Whether Emily was telling the truth or not about believing that Charles was dead in 1859 is not relevant; she was, in fact, still married to Charles in 1859 and thus never legally married to Sanford. (By the way, the Charles Finnemore to whom Emily was married in 1854 was not Amherst’s Charles Finnemore. Charles Augustus Finnemore of Amherst was born about 1836, about ten years younger than Emily’s husband.)

What about Nancy Newport? It seems that Nancy did not apply for widow’s benefits right after the war. Her name first shows up in the pension record when she applied for benefits in 1913! She claimed to have been married to Sanford Jackson in Worcester in 1860. She never could produce a marriage certificate, though she did give a specific date (June 3, 1860) and the name of the Justice of the Peace who had performed the ceremony. However, the City Clerk of Worcester could find no record of her alleged marriage to Sanford. Without better evidence, Nancy’s application was repeatedly rejected, though she kept trying until at least 1926, by which time she was about 90 years old. Recent examination of the 1860 U.S. census shows 15-year-old Nancy Newport living in Ludlow, Massachusetts, while her purported husband Sanford Jackson was living in Worcester County. Although that census did not ask marital status, it has a column to be checked if “married within the year”. The enumeration occurred in July and August, after the date of their supposed June wedding, but neither Sanford nor Nancy had that box checked.[31]

So it seems that neither “wife”, Emily or Nancy, ever received a significant amount of money as widows, although perhaps Emily did briefly receive benefits before Polly stepped in. However, Sanford Jackson’s mother, Polly, did receive Sanford’s back pay and his $100 enlistment bounty.[32]

For more information on the kidnapping of free Black people, please see this article:

Also: Wells, Jonathan Daniel, The Kidnapping Club, Bold Type Books, New York, 2020.

Cliff McCarthy, Archivist at the Lyman & Merrie Wood Museum of Springfield History and at the Stone House Museum in Belchertown, is also Vice-President of the Pioneer Valley History Network.

[1] Smith, James Avery, The History of the Black Population of Amherst, Massachusetts, 1728-1870, New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston, 1999, p. 23.

[2] Smith, James Avery, The History of the Black Population of Amherst, Massachusetts, 1728-1870, New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston, 1999, p. 106.

[3] Smith, James Avery, The History of the Black Population of Amherst, Massachusetts, 1728-1870, New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston, 1999, p. 23.

[4] Parmenter, C. G. “Why Angeline Didn’t Go: A True Tale of Slavery Days”, Springfield Sunday Republican, 2 August 1896.

[5] Stone House Museum, Belchertown, MA, biographical material in vertical file, “Mason Shaw”.

[6] Vital Records of Belchertown, Corbin Collection, Volume 1, New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston, 2003, (CD-ROM).

[7] 1820 U.S. Census for Mason Shaw, (Castine, Hancock Co., Maine).

[8] For more information on Charles Cheney and Mt. Healthy, see: http://hamiltonavenueroadtofreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/HAMILTON-AVENUE-map-and-text.pdf

[9] Vital Records of Belchertown, Corbin Collection, Volume 1, New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston, 2003, (CD-ROM).

[10] Augusta {GA] Chronicle, 9 January 1840, p. 3.

[11] Smith, James Avery, The History of the Black Population of Amherst, Massachusetts, 1728-1870, New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston, 1999, p. 23.

[12] Lombardo, Daniel, “They Risked Jail for the Freedom of a Black Girl” in A Hedge Away, Daily Hampshire Gazette, Northampton, MA, 1997.

[13] Smith, James Avery, The History of the Black Population of Amherst, Massachusetts, 1728-1870, New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston, 1999, p. 24.

[14] Parmenter, C. G. “Why Angeline Didn’t Go: A True Tale of Slavery Days,” Springfield Sunday Republican, 2 August 1896.

[15] Parmenter, C. G. “Why Angeline Didn’t Go: A True Tale of Slavery Days”, Springfield Sunday Republican, 2 August 1896.

[16] Parmenter, C. G. “Why Angeline Didn’t Go: A True Tale of Slavery Days”, Springfield Sunday Republican, 2 August 1896.

[17] Smith, James Avery, The History of the Black Population of Amherst, Massachusetts, 1728-1870, New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston, 1999, p. 25.

[18] Woodward, Hobson, “The Abduction of Angeline,” Daily Hampshire Gazette (Weekend Living section), 1-2 August 1998.

[19] Smith, James Avery, The History of the Black Population of Amherst, Massachusetts, 1728-1870, New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston, 1999, p. 28.

[20] Smith, James Avery, The History of the Black Population of Amherst, Massachusetts, 1728-1870, New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston, 1999, p. 28.

[21] “Commonwealth v. Henry Frink, et al”, Hampshire Court of Common Pleas, Book 28, Pgs 571-572, March 1841.

[22] Woodward, Hobson, “The Abduction of Angeline,” Daily Hampshire Gazette (Weekend Living section), 1-2 August 1998.

[23] Smith, James Avery, The History of the Black Population of Amherst, Massachusetts, 1728-1870, New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston, 1999, p. 30.

[24] Woodward, Hobson, “The Abduction of Angeline,” Daily Hampshire Gazette (Weekend Living section), 1-2 August 1998.

[25] Smith, James Avery, The History of the Black Population of Amherst, Massachusetts, 1728-1870, New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston, 1999, p. 86-87.

[26] Vital Records for Amherst, Massachusetts, available online at Ancestry.com.

[27] 1855 Massachusetts State Census for Catharine Jackson, (Amherst, Hampshire Co., MA).

[28] Vital Records of Monson, “Massachusetts: Vital Records, 1841-1910,” available online at AmericanAncestors.org.

[29] Smith, James Avery, The History of the Black Population of Amherst, Massachusetts, 1728-1870, New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston, 1999, p. 86-87.

[30] Romer, Robert H., email to the author, 22 November 2013.

[31] 1860 U.S. Census for Phebe Newport (Ludlow, Hampden Co., MA) and William B. Bliss (Warren, Worcester Co., MA).

[32] Romer, Robert H., email to the author, 22 November 2013.