Module 2: Behavior Change

Behavior Analyst Certification Board Registered Behavior Technician™ (RBT®) Task List 2nd Ed.

C-03 Use contingencies of reinforcement (e.g., conditioned/unconditioned reinforcement, continuous/intermittent schedules)

Consequences: Reinforcement and Punishment

In Module 1, we reviewed that consequences are stimulus changes or environmental conditions that occur immediately after a behavior. Two types of consequences are reinforcement and punishment. As one of the most important principles of behavior analysis, the process of reinforcement entails a consequence that increases the future likelihood of the behavior it follows. Such behavior change occurs over time following immediate reinforcement. Paraprofessionals who understand the principles of reinforcement can easily and efficiently teach their clients new skills. Conversely, the process of punishment entails a consequence that decreases the future likelihood of the behavior it follows. Although we will briefly cover the process of punishment later in this module, the focus of this module will be reinforcement as it is integral to all behavior analytic teaching strategies.

Positive and Negative Consequences

When referring to consequences, positive and negative are used to qualify the type of reinforcement or punishment. Positive, meaning the addition of a stimulus following the target behavior, and negative, meaning the removal of a stimulus following the target behavior. Positive and negative do not refer to a consequence being “good” or “bad”, instead, positive and negative should be thought of as they are in mathematical equations: the addition or subtraction of a stimulus (Figure 2.1).  Figure 2.1: Four Types of Consequences

Figure 2.1: Four Types of Consequences

Positive Reinforcement

Positive reinforcement is the process that occurs when a desirable stimulus is added following the behavior, thereby increasing that behavior. For example, James says, “please” when requesting an item followed by his teacher providing a sticker. If James continues to say “please” when requesting an item, positive reinforcement has occurred. Any behavior can be reinforced, therefore both desirable behavior, as well as undesirable behavior, may be reinforced. If behavior is increasing or maintaining, then reinforcement is occurring in relation to the particular behavior. In the example above, saying “please” was a skill that was positively reinforced by the teacher. However, a client may also learn to engage in challenging behavior, such as aggression in the same manner. For example, if James bites his teacher and his teacher then presents preferred items, perhaps in an effort to “calm him down”, and his biting behavior increases over time, challenging behavior can be positively reinforced. Therefore, in the moment it may make the biting behavior cease, however in this example, the behavior increased over time, indicating that positive reinforcement occurred, and a challenging behavior had developed. As one can see, this is how undesirable behavior may be inadvertently reinforced, causing a need for treatment in the future. Therefore, knowledge regarding how behavior works can not only assist with the treatment of behavioral issues but also help with the prevention of undesirable behavior from being established in the first place.

Negative Reinforcement

When a stimulus is removed following a response and in turn increases the future likelihood of the behavior, the process of negative reinforcement has occurred. For example, Sally has broccoli (a non-preferred food) on her plate. Sally cries. Her mom removes the broccoli from her plate. In the future, if Sally cries more often when broccoli or other non-preferred foods are presented, her crying behavior was negatively reinforced. Negative reinforcement is typically associated with an undesirable stimulus being present before the behavior occurs (antecedent) and the behavior increases due to the removal of the undesirable stimulus as a consequence to the behavior. Other examples of negative reinforcement may be pressing the snooze button on an alarm clock, rolling down a window in a hot car, or doing chores following a parent nagging. The future likelihood of these behaviors increases with the removal of a stimulus the person finds undesirable (e.g. the sound of the alarm, heat, parent nagging).

Reinforcers

A consequence stimulus that increases the target behavior it follows is referred to as a reinforcer. There are two categories of reinforcers: unconditioned and conditioned. An unconditioned reinforcer is not learned during an organism’s lifetime (e.g., food water, warmth) and may also be referred to as an unlearned or primary reinforcer. A conditioned reinforcer is acquired during an organism’s lifetime (e.g., stickers, tokens, money) and may also be referred to as a learned or secondary reinforcer. Neutral stimuli can become conditioned as a reinforcer via pairing with an unconditioned reinforcer.

Examples of Positive Reinforcers

Tangibles Engaging in activities without others may serve as tangible reinforcement. Any item can be a tangible reinforcer even if it is not used as designed or intended. Playing with a toy car or putting together a puzzle are examples of tangible activities. Edible reinforcers are examples of tangible items that can function as reinforcers. Preferred edibles can be beneficial because they are primary reinforcers, can be delivered immediately and are suitable for clients who have minimal activity preferences. The use of edible reinforcement requires consent from parents/guardians. Consideration should be given to client allergies and dietary restrictions and only the healthiest options and portions should be used. Excessive use of edibles may be considered harmful. When using edible reinforcement, other items and/or praise should be paired to condition alternative reinforcers. Social Positive Reinforcers When social attention increases desired behavior, it can be considered a reinforcer. Eye contact, proximity, direct physical or verbal contact with peers or adults could all be considered social positive reinforcers. Engaging in activities with others may also serve as social positive reinforcement. Board games, high fives, and conversation are all examples of social positive reinforcers. Automatic Positive Reinforcers (Sensory) Anything that can be used to stimulate the five senses (sight, smell, taste, feeling, hearing) could be considered reinforcement. The light produced by waving a glow wand, the sound of music produced by hitting the keys of a piano, and the scent from smelling a lavender satchel could all be considered automatic positive or sensory reinforcers.

Video 1: An example of praise delivered as a reinforcer for correct responding

Video 2: An example of praise and a tangible delivered as a reinforcer for correct responding

Schedules of Reinforcement

A schedule of reinforcement is a rule that describes the contingency by which behavior will produce reinforcement. It can be defined by the time which passes (interval) or the number of responses emitted (ratio) since the previous reinforcement was delivered (Ferster & Skinner, 1957). Much of B.F. Skinner’s early work indicated that the rate of responding can be determined by the schedule of reinforcement in effect (e.g., Ferster & Skinner, 1957; Skinner, 1938) and identifying when to provide reinforcement for a target behavior is important to teaching skills to others. Continuous Reinforcement (CRF) In a CRF schedule, reinforcement is provided contingent on each occurrence of the target behavior. The benefit of this schedule is that it produces a high rate of responding. It may, therefore, be most beneficial when teaching new skills (Cooper, Heron & Heward, p. 305).

Example: Every time Julia turns the faucet on, water comes out and she fills her water bottle. Julia continues to turn the faucet on when she is thirsty to fill her water bottle.

Example: A client is learning to gain attention from others. Every time the client says “Excuse me” attention is provided. This skill increases over time.

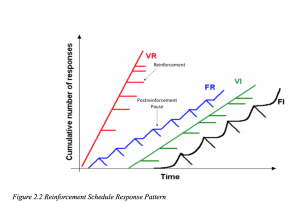

Intermittent reinforcement (INT) Reinforcement is provided only for some occurrences of the target behavior. Below are four types of basic intermittent schedules of reinforcement. Fixed Ratio (FR) Reinforcement is provided after the completion of a predetermined number of responses. Therefore, the quicker the completion of the ratio requirement, the sooner reinforcement is delivered (Cooper, Heron & Heward, p. 306). Research has shown that the effects of this type of reinforcement are that it produces high rates of consistent responding followed by a post-reinforcement pause before responding is resumed again. See figure 2.2 for an illustration of the post-reinforcement pause pattern during an FR schedule response pattern. Please note, a fixed ratio of 1, or an FR1, is synonymous with CRF, as it means that reinforcement is provided after every response. Whereas, an FR2 (delivery of reinforcement after every 2 responses) and higher denotes an INT schedule of reinforcement.

Example: After every 100 sales made, Hector receives an immediate notification email from his company praising his hard work and a $500 bonus. Example: During a discrete trial training program, a small edible and praise are provided after every 5 correct responses. This would be an FR5 schedule of reinforcement.

Variable Ratio (VR). Reinforcement is provided after a predetermined variable number of responses with a specified mean value (Catania, 1998). For instance, a VR5 means that reinforcement is provided an average of every 5 responses. Therefore, sometimes it is provided for 2 responses, or 7 responses and so forth as long as the mean is equivalent to 5 responses. The effects of VR schedules are steady, quick rates of responding because the individual is unsure of exactly which response will produce reinforcement (Cooper Heron & Heward, p. 309).

Example: Every so often when Angela logs into her social media site, she receives a notification from a connection or likes to recent posts. As a result, this increases the frequency of logging into her social media account. Example: Throughout the day, a small edible and praise are provided after an average of every 4 appropriate interactions a client engages in. This would be an VR4 schedule of reinforcement.

Fixed Interval (FI). Reinforcement is provided for the first response following a fixed duration of time (Catania, 1998). Therefore, an FI 2-minute schedule, denotes reinforcement being provided for the first response emitted after 2 minutes has elapsed. This schedule of reinforcement results in a post-reinforcement pause at the beginning of the interval, with responding accelerating towards the end of the interval (Cooper, Heron & Heward, p. 310-311), creating the scallop pattern shown in figure 2.2.

Example: Oscar enters the wrong password into his secure lap top. A message pops up indicating that he can try to log-in again in 3 minutes. His first correct log-in attempt after 3 minutes elapses is reinforced with access into his computer. Example: A child requests to play a game and receives permission for the first request after 30 minutes has elapsed. This is considered an FI 30-minute schedule.

Variable Interval (VI). Reinforcement is provided for the first response after a mean duration of time (Catania, 1998). Therefore, a VI 30-second schedule indicates that reinforcement is provided on average after the first response occurs each time 30 seconds elapses. So, reinforcement may be provided after 10 seconds or 40 seconds and so on, if the mean reinforcement equals 30 seconds. The use of this schedule may result in a constant but low to moderate rate of responding. This rate of responding is sensitive to the average length of the interval. Therefore, the longer the interval is, the lower the response rate will be (Cooper, Heron & Heward, p. 312-313).

Example: A rat pressing a lever in an experimental chamber receives a pellet of food from the dispenser for the first response that occurs after an average of 1 minute. This is considered an VI 1-minute schedule. Example: A child requests attention and receives attention for the first request after an average of 5 minutes has elapsed. This is considered an VI 5- minute schedule.

Figure 2.2 Reinforcement Schedule Response Pattern

Parameters of Reinforcement

Reinforcement is most effective when it meets the following parameters (Cooper, Heron, & Heward, p. 286-289). Immediate reinforcement Immediate reinforcement strengthens the behavior that it immediately follows. If reinforcement does not occur immediately after a behavior, other behaviors may occur during the delay between the target behavior and reinforcement. As a result, another behavior may inadvertently be reinforced instead of the target behavior. For example, if a paraprofessional asks a client to touch their head, then the paraprofessional turns around to get a tangible reinforcer in the cupboard, and finally provides the reinforcer as the client is scratching their belly, the paraprofessional has likely reinforced belly scratching rather than head touching. Sufficient magnitude Magnitude is defined as “the duration of time for access to the reinforcer, the number of reinforcers per unit of time (reinforcer rate), or the intensity of the reinforcer.” (Cooper, Heron, & Heward, p. 286). Therefore, if a client is provided with one small marshmallow they may be likely to perform a simple addition problem for such a reinforcer. However, if you provide one small marshmallow for the completion of an entire math worksheet, the magnitude may not be sufficient to act as a reinforcer. In this case, several marshmallows, a larger marshmallow or an entirely different reinforcer may be necessary to increase the likelihood of completing an entire worksheet. Therefore, a reinforcer for one behavior or for a certain number of responses may not be a reinforcer for a different behavior or when a greater response effort is required (e.g., engaging in a behavior or for a longer duration, an increase in the chain of behaviors or repeated instances of a specific behavior) require a reinforcer with a greater magnitude than behavior requiring less response effort. Preferred Reinforcement is effective if the reinforcer is preferred by the individual. Preference is person-specific, meaning that what one person prefers another person may not. Preference for specific items may also wax and wane over time, over a few days or even within a session (Logan & Gast, 2001). For example, identifying preferred stimuli and using them to teach new skills makes it more likely that the stimuli may function as a reinforcer and increase the occurrence of the skill over time. However, it is important to note that just because a stimulus is preferred does not automatically mean the stimulus is also a reinforcer. If, and only if, it increases responding contingent on the target behavior may it be called an actual reinforcer (Green et al., 1998, 1991; Logan et al., 2001; & Leatherby et al., 1992). In Module 6, we will review preference assessment methods to use with your clients for this purpose. Variable The value of a reinforcer can be momentarily altered. Satiation decreases the value of a reinforcer because a client has received too frequent access to the reinforcer. For example, if a client is toilet training and an electronic device (e.g., Kindle, iPad) has been identified as a reinforcer for remaining seated on the toilet, but the client has free access to this device outside of training sessions, the client may not engage in the desired behavior of sitting on the toilet. In this situation, the value of the reinforcer is low, given that he receives access to the device throughout the day. While satiation decreases the value of a reinforcer, deprivation increases the value of a reinforcer because the client has minimal or no access to the reinforcer for a period of time. In the previous example, the client was satiated from free access to the electronic device throughout the day resulting in a lack of engagement in the desired behavior to earn electronics. If that same client only received access to the device when they were seated on the toilet, the client may be more likely to engage in the desired behavior to gain access to this isolated reinforcer, given that this is the only way that access to electronics is provided. Presenting a variety of reinforcers can prevent satiation. Providing access to novel reinforcers may also help control for the effects of satiation (Logan et al., 2001). Consistently implemented Earlier in this module, you learned that the schedule of reinforcement can affect the frequency and accuracy of responding. When reinforcement is provided consistently following the target behavior, responding increases and lasting behavior change can occur.

Punishment

As a reminder, punishment is a consequence that immediately follows a behavior and decreases the future likelihood of the behavior. As with reinforcement, there are two types of punishment: positive and negative. When considering the use of punishment, the client’s rights to a safe environment, effective treatment, use of least restrictive interventions, and adherence to legal policies should be evaluated before its implementation. Further review of the ethical considerations surrounding punishment will be discussed in Module 7. Punishment should not be confused with extinction.

Extinction involves withholding reinforcement for a previously reinforced behavior and will be discussed further in Module 4 when we cover differential reinforcement. The Behavior Analyst Certification Board® (BACB™) has developed The Professional and Ethical Compliance Code for Behavior Analysts (2016) that outlines a process for the use of least restrictive procedures. Specifically, Code 4.08: Considerations Regarding Punishment Procedures details the ethical responsibilities required of Behavior Analysts for its use. In Module 7, we will review the Professional and Ethical Compliance Code requirements for RBTs. However, it is important to note that the field of ABA utilizes the least restrictive treatment approach, meaning that reinforcement procedures are generally the first course of treatment unless safety is a concern. This is an effective and humane treatment approach. Therefore, the punishment procedures we will briefly review in this section should not be withheld from a client whose behavior presents serious harm to themselves or others. In addition, being that our clients have the right to effective treatment, if reinforcement alone has not effectively treated severe challenging behaviors, punishment procedures should be used in conjunction with reinforcement procedures to effectively treat the behavioral issue. One of the reasons for this is because punishment generally teaches an individual which behaviors not to engage in, therefore reinforcement is necessary to teach them which behaviors to engage in to access reinforcers appropriately.

Positive Punishment

When an undesirable stimulus is presented following the target behavior and decreases the future likelihood of the behavior, positive punishment has occurred. For example, while in the grocery store, a child repeatedly requests a candy bar and the parent sternly screams “No!”. If the child’s requests for a candy bar in the grocery store decrease in the future, positive punishment as occurred. In this case, the parent screaming “No” served as the addition of a stimulus that decreased the child continually requesting the candy bar in the grocery store.

Negative Punishment

Negative punishment is the removal of a desirable stimulus contingent on a target behavior that decreases the future likelihood of the behavior. For example, Cheri just received her driver’s license. She was caught speeding and was given a ticket. As a result, of the ticket, her parents took her driving privileges away for one month. If Cheri’s speeding behavior decreases, then the removal of driving privileges decreased the future likelihood of speeding, indicating that the process of negative punishment has occurred.

Punishers

Like reinforcers, there are two types of punishers: unconditioned punishers and conditioned punishers. An unconditioned punisher serves as punishment without being learned during one’s lifetime. Other terms for unconditioned punishers are primary punishers or unlearned punishers. Pain, extremely loud noises, and extreme temperatures could all be considered unconditioned punishers. Conditioned punishers are stimuli that are learned to have punishing properties via pairing. Neutral stimuli are paired with unconditioned punishers and thereby became conditioned punishers. Other terms for unconditioned punishers are primary punishers or unlearned punishers. For example, the sight of blood may become a conditioned punisher for some individuals, given that it is often paired with pain or other unconditioned punishers. Another common example of a conditioned punisher is a reprimand such as “You better stop that” or “No, don’t do that!” and other forms of social disapproval (e.g., shaking one’s head contingent on another person engaging in an undesirable behavior). In fact, a reprimand is called a generalized conditioned punisher because it has been paired with various unconditioned and conditioned punishers in the past. Like reinforcers, what is a conditioned punisher for one individual may not be a conditioned punisher for another individual, and what is punishing to one behavior may not be punishing to other behaviors in an individual’s repertoire. For example, lemon juice was shown to be an effective punisher in previous studies (e.g., Cipani, Brendlinger, McDowell, & Usher, 1991; Gross, Wright, & Drabman, 1981), however, other individuals may find lemon juice desirable and it can therefore function as a neutral stimulus or even a reinforcer for that individual’s behavior.

Common Types of Punishment Procedures

Although there are several methods that can be considered punishment interventions, some of the common interventions are described below:

Positive Punishment Procedures

Response Blocking and Redirection In this procedure, the paraprofessional physically prevents the behavior from occurring and neutrally redirects to more appropriate behavior. Response blocking can be used alone; however, it is recommended that it be paired with redirection whenever possible, to decrease the likelihood of collateral behaviors (e.g., aggression) due to blocking alone (e.g., Hagopian & Adelinis, 2001). In addition, in Module 3, we will discuss how to use response blocking as part of an errorless teaching procedure.

Overcorrection

In this procedure, the client is either required to repair or restore the environment to its original condition and then engage in behavior that will improve the environment (restitutional overcorrection) or engage in the desired behavior repetitively after the occurrence of undesirable behavior (positive practice overcorrection). For example, if a client engages in property destruction in their classroom, they may be required to clean not only what they destroyed, but additional areas within their classroom.

Reprimands

Reprimands contingent on a response may have a punishing effect on the behavior it immediately follows. For example, in the previous positive punishment example, the parent screaming “No!” in response to the child’s request, decreased the frequency of that behavior, thus making the reprimand a punisher.

Negative Punishment Procedures

Time-out In general, time out is a period of time when reinforcement or earning reinforcement is made unavailable contingent on undesirable behavior. For instance, if a child throws a preferred toy and his toys are removed and made unavailable for 5 minutes contingent on each instance of throwing this would be an example of time out. Likewise, if a child hits his mother and is placed on a chair without access to social attention or toys for 3 minutes this is also an example of time out from reinforcement. Response cost Response cost entails a loss of a specific amount of reinforcement contingent on an undesirable behavior resulting in a decrease in the undesirable target behavior. An example of this procedure is a child earning 30 minutes of playground time and losing 10 minutes of playground time contingent on each instance of hitting one of his friends.

Conclusion

The use of reinforcement is integral for effective and lasting behavior change. Furthermore, although there are ethical considerations for the use of punishment, it may also be necessary for effective behavior change. Throughout the remainder of this curriculum, we will review how the effective use of reinforcement and other ABA strategies can be used to increase socially significant behavior. Links to Quizzes for Module 2: Quiz 1 Quiz 2

References

Behavior Analyst Certification Board (2016). Professional and Ethical Compliance Code for Behavior Analysts. Retrieved from www.bacb.com.

Catania A.C. (1998) Learning [4th] ed. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey.

Cipani, E., Brendlinger, J., McDowell, L., & Usher, S. (1991). Continuous vs. intermittent punishment: A case study. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 3(2), 147-156. Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2007).

Applied Behavior Analysis (2nd ed.). Columbus, OH: Merrill Prentice Hall.

C. B., & Skinner, B. F. (1957). Schedules of reinforcement.

Green, C. W., Reid, H. D., Canipe, V. S., and Gardner, S. M. (1991). A comprehensive evaluation of reinforcer identification processes for persons with profound multiple handicaps. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, (4) 537–552.

Green, C. W., Reid, D. H., White, L. K., Halford, R. C., Brittain, D. P., and Gardner, S. M. (1988). Identifying reinforcers for persons with profound handicaps: Staff opinion versus systematic assessment of preferences. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, (21) 31–43.

Gross, A. M., Wright, B., & Drabman, R. S. (1981). The empirical selection of a punisher for a retarded child’s self-injurious behavior: a case study. Child Behavior Therapy, 2(3), 59-65.

Hagopian, L. P., & Adelinis, J. D. (2001). Response blocking with and without redirection for the treatment of pica. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 34(4), 527-530.

Logan K. R., Jacobs, H. A., Gast, D.L., Smith P. D., Daniel J., & Rawls J., (2001). Preferences and Reinforcers for Students with Profound Multiple Disabilities: Can We Identify them? Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, (2), 97. doi:10.1023/A:1016624923479

Logan K. R., & Gast, D. L., (2001) Conducting Preference Assessments and Reinforcer Testing for Individuals With Profound Multiple Disabilities: Issues and Procedures. Exceptionality, 9 (3) 123-134. DOI: 10.1207/S15327035EX0903_3

Leatherby, J. G., Gast, D. L., Wolery, M., and Collins, B. C. (1992). Assessment of reinforcer preference in multi-handicapped students. Journal of Developmental Physical Disabilities 4: 15–36. Manske, M. (2012). Schedule of reinforcement.PNG. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Schedule_of_reinforcement.png.

Skinner, B. F. (1938). The behavior of organisms: an experimental analysis. Appleton-Century. New York.