Recently, I visited my perippa and perimma’s (uncle and aunt’s) farm in a small town called Sathyamangalam — Sathy in short. Sathy is one of a series of agricultural towns in the southern state of Tamil Nadu along the Bhavani River, a tributary of the better-known Cauvery. On either side of the roads in this region, you’ll find plots of banana trees organized in neat rows, rice paddies sparkling with water, and – ever pleasing to look at – tall coconut trees with their thin, elegantly curving trunks.

The farm in Sathy has been and continues to be a special place for everyone in my extended family. I’ve always felt welcomed and at home there, and my perippa and perimma have guided me through some vexing and important personal decisions. I’ve been visiting the farm since middle school. When I went to college in Tiruchirappalli (also in Tamil Nadu), I used to take inter-city buses to Sathy during the holidays. Even after moving to the United States, I’ve managed to return once in a few years.

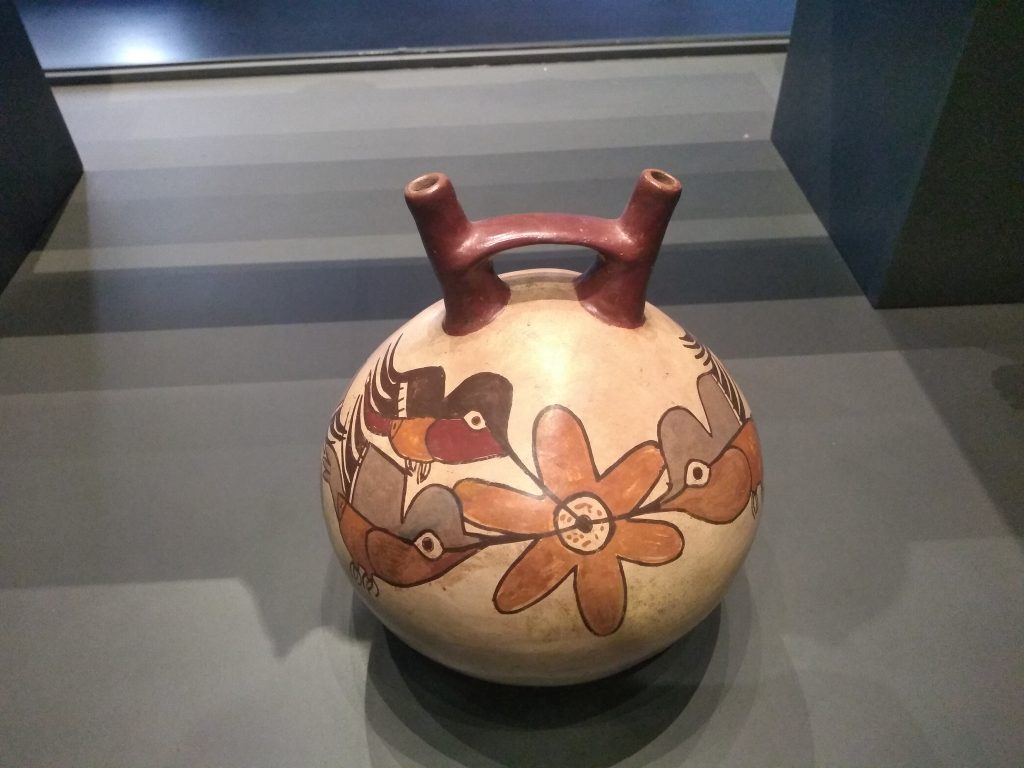

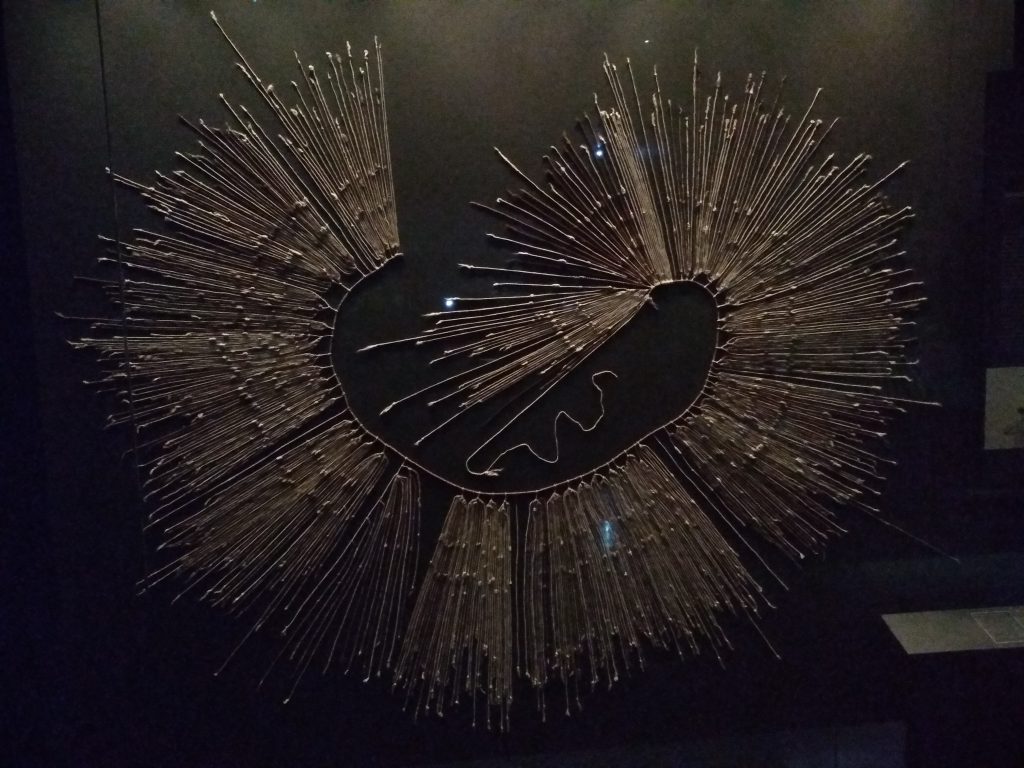

As a town, Sathy has grown considerably, but the farm still looks about the same. There’s the white house with the slanting red roof that comes into view soon after you enter the dirt road off the highway; there’s the spacious patio where my perippa often sits to work these days. Walk around a bit and you run into the sheds for the cows, the wells for water, and the rectangular plots for crops — turmeric, coconut, areca nut this year, and in the past rice, sugarcane, and Casuarina trees. I love standing on a ledge of the wells to see the steeply rising mountains in the distance. The cloudy weather on the days that I visited only enhanced the beauty of the farm. I spotted kingfishers, peacocks, owls, and woodpeckers with little effort. The place felt more a wildlife preserve than a place for cultivation.

My perippa’s family has owned the farm for at least two centuries. In the 1960s, with the coming of the Green Revolution and high-yielding crop varieties to India, the family started to use synthetic fertilizers and pesticides. Perippa wholeheartedly adopted these newer Western methods: what he now calls “chemical farming”. His brother worked in Rallis, a company that sold agricultural products. The farm served as an informal center for R&D. Agricultural scientists and researchers from Rallis visited Sathy to test the effectiveness of the company’s products.

In the 1990s, however, after noticing the detrimental effects of chemical farming on soil health – and in fact his own health – perippa shifted to organic farming. Perimma has jointly managed the farm since her marriage in 1973 and has been an equal partner in this transformation. The two of them have turned the 10-acre plots into a model organic farm, now famous in southern India.

Every day my perippa – now 82 years old and unmistakable in his lean, upright frame – attends to a constant stream of messages and calls from other farmers who need his assistance. His six decades of experience, equally split between chemical and organic farming, is highly valued. Visitors from far-off villages drop by unannounced. He is invited often to give seminars and workshops in Tamil Nadu and other states. There are plenty of YouTube videos (in English as well as Tamil) in which he tells his story. (The first video has some good views of the farm.)

In all his interviews, perippa credits other farmers who have successfully tried alternative cultivation approaches and whose methods he adapted. Names that often come up include G Nammalvar, an early pioneer of organic farming in Tamil Nadu; Shripad Dabholkar of Maharashtra (whose book Plenty For All has been a major source of inspiration); Bhaskar Save of Gujarat; and Narayana Reddy of Karnataka (who often visited the Sathy farm to provide guidance; Reddy, in turn, was influenced by Masanobu Fukuoka’s One-Straw Revolution). In investigating the life and work of these farmers, I got the impression that a robust response to the negative effects of the Green Revolution had quickly emerged in India. Today, however, the declining labor supply in agriculture poses a bigger challenge: no one aspires to be in farming anymore, and all over India, there’s been a hollowing out in rural areas as people move to urban centers.

§

I would often mention the Sathy farm with great pride to my friends in the United States. However, the truth is that I didn’t really know (and still don’t know) the basics of agriculture. Perippa often explained his techniques when I visited, and though I sensed his passion each time, I had not made the effort to follow the details. But this time was different. This time, when he took me around the farm, bent down to pick a handful of topsoil and explained how his goal was to increase the diversity of microorganisms in it; or plucked a plant to illustrate the structure of tap and feeder roots; or described how he was using certain plant species called cover crops to fix much-needed nitrogen in the soil – this time, I tried to learn as much as I could, and there was far greater emotional resonance.

What’s changed in the last few years is my curiosity about the history of life on Earth and how all life is interrelated. At its core, perippa’s organic farming vision was to create a healthy soil environment that allowed symbiotic relationships between plants, fungi, insects, and micro-organisms to prosper. These relationships, in which there is a lot of give and take of nutrients, are hundreds of millions of years old. For instance, plants provide carbon to fungi living in their roots; in exchange, the fungi extract nutrients such as phosphorous from the soil, which the plants absorb. In popular culture, evolution is often presented as a competitive struggle for survival and it is to some extent that. But there are also myriad examples of species collaborating in mutually beneficial ways. We are yet to fully fathom the magnitude and complexity of such partnerships.

I’d read about these concepts in books such as Lynn Margulis’s Symbiotic Planet and Merlin Sheldrake’s Entangled Life. The great pleasure of my visit to Sathy was to see these concepts in action. I still don’t understand enough about farming but if I do learn something in the future – that’s a big if, given my academic commitments! – then I’ll view this trip as a true start.

_____

I took all the pictures above except for the picture of my perimma — that’s from an article in the newspaper The Hindu in which she was interviewed about traditional varieties of rice. (Unfortunately, this article is behind a paywall.)