By Angela Yu

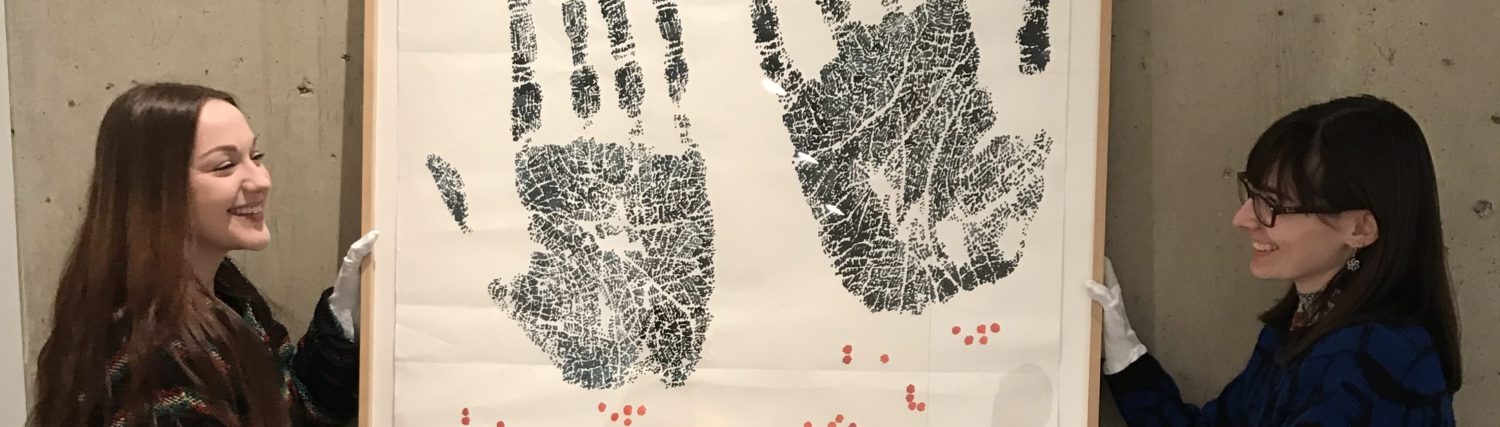

Robert Motherwell, Untitled, from the Basque Suite, 1970, ink and acrylic on paper. Mount Holyoke College Art Museum. Gift of David and Renee Conforte McKee (Class of 1962), MH 2000.10.2.

Abstract Expressionist or abstract art is not always a direct channel for the artist’s individual desires and needs. Whether the artist consciously or unconsciously knows this or not, in making their works, their works of art convey the artist’s yearning to be understood or seen by the world, just as art is an attempt to understand and respond to the environment around it. A close examination of Robert Motherwell’s Untitled, from the Basque Suite, 1970, ink and acrylic on paper, and Hassel W. Smith’s Drawing 1962, 1962, ink and wash, reveals narratives of growth and the relationship of the individual to the community in each, communicated in different ways through subtle details of form and composition.

Hassel Wendell Smith, Jr., Drawing 1962, 1962, ink and wash on paper. University Museum of Contemporary Art, University of Massachusetts, Amherst. University purchase, UM 1967.16.

The community is the origin and place in which individuals rise together with or without. With growth and hope to rise above limitations inevitability comes departure. While both works thematize the relationship between individual freedom and community through the relationship of marks and gestures, Motherwell’s Untitled conveys a communal togetherness and migration, which seems to symbolize a social context in which everyone comes from a common ground and rises together to move to the next destination. Smith’s Drawing 1962, on the other hand, expresses a dramatic and adventurous departure of an individual from community in favor of independence. The viewer is drawn into the paper and experiences the stages of growth. Despite their flatness in both medium and aesthetics, both drawings allow the viewer to experience both temporal and sensual experiences, which seem to transform the flat surface of the paper into a virtual, three-dimensional space. Viewers are invited to participate in an adventure of growth and departure.

In both drawings, the black masses and the edge of the papers set the stage for the location and dynamic performance of departure. In Untitled, the journey might begin with two long, horizontal lines on the foreground, with an arrow-like form made of two large brushstrokes leading the eye upward and across the expanse of the paper. On the other hand, focusing on the direction of the artist’s brushstrokes, Drawing 1962 begins from the top where short, immediate strokes clutter together. Untitled gives a sense of ease as the ground, made of two horizontal green and black lines, conveys a sense of beginning. The green line placed on the lower end of the paper evokes the image of a grass lawn. The first long, horizontal line appears to go on endlessly. It is echoed by a second black line above, which reinforces this sense of balance and harmony. Drawing 1962 begins with built-up momentum from the tension between individual, short strokes, applied quickly on top of one and another in various directions to create a black mass with sharp edges. The lines appear almost to burst apart at the seams.

At the same time, the composition relies on the viewer to develop their own interpretation. Untitled relies on knowledge of nature and pictorial familiarity, in which the ground is the primary foundation from which everything else grows. The intense green color immediately stands out from the monochrome forms and draws the viewer’s attention. Drawing 1962 relies more on detail and chaos as a starting point, in that the area with more detailed coverage draws attention first. It mimics the normal direction of reading a text, from top to bottom, in locating where the movement begins. It is more difficult to read Untitled from top to bottom. Instead, the viewer tends to mimic the upward and downward diagonal vectors of the arrow-like form, and potentially become diverted by the translucent masses inside it. The forms suggest a natural, communal growth in which the black masses ascend upwards. In Drawing 1962, in reading the work from top to bottom, the viewer mimics the downward motion of the stroke and gets a sense of the weight of gravity pulling the eyes away from the chaotic clutter and towards independence.

In both drawings, there is a main subject or “performer” that goes through the stages of departure. In Untitled, translucent, organism-like forms slowly rise from the surface and towards the primary arrow-like form. Each form appears to have its own distinct identity, with different shapes, sizes, and paces and yet, they seem to be moving together towards a common location. In Drawing 1962, every form seems to be a part of a whole organism, manifesting only to be dispersed in various directions downward, with the bent, cylindrical form and geometric form as coupled performers. Untitled appears balletic, elegant, and smoothly paced, while Drawing 1962 seems acrobatic, dramatic, and fast-paced.

In Untitled, the translucent forms appear to fly slowly on a gentle upward slope. The larger translucent form, closest to the ground, excretes a series of lines from its body as though to indicate the start of its transformation or flight upwards. Coupled with their gentle slope positions, the lines convey the elasticity and plasticity of the forms, which all mark the beginning of departure and a slow-paced transformation. On the left of the larger form, a small, darker form hangs at the end of a thin, elongated form that must have already passed through the arrow-like barrier. The small string or line connecting the elongated form and the small form attached below it demonstrates an elasticity and process of transformation.

Meanwhile in Drawing 1962, a large, cylindrical form protrudes out of the chaotic clutter at the top and with one sweeping motion, and curves to the right in a strenuous effort to move upward and push against the weight of gravity. Underneath this phallic form is a geometric structure that appears to have broken off from the cylindrical form. With proximity to one and another, the two forms, like acrobats, synchronize in their movement in midair. On the upper section of the paper, a collective of thin lines together with a third phallic structure move toward the cylindrical form. Suspense is created as the drawing suggests a potential collision.

In both drawings, color values help establish a sense of depth, with the darkest forms in the foreground and the least saturated in the background. In Untitled, the horizontal band of green and black are most heavily pigmented, followed by the arrow-like form, and finally the translucent forms. The foreground welcomes the viewer by establishing a starting or resting place, the green field. In Drawing 1962, the foreground confronts the viewer with ink splatter and a solid, geometric form. The viewer gets a sense of forms being swung across a three-dimensional space and out towards them.

The drawings convey different temporal experiences: Untitled is slow while Drawing 1962 is rapid and immediate. The pacing is conveyed through the method of ink application in creating the effect of blur or fading. For on the long, black masses in Untitled, Motherwell exercised a smoother application with a very wet tool that required less force and control. He applied wide and broad strokes on the large arrow and let the ink wash penetrate through the paper. His process is recorded in the blur and light splotches (and stains) inside the arrow-like mass, which indicate a gradual ink movement. However, in the upper right section of Drawing 1962, Smith created a blur effect through a controlled process of directly rubbing the ink on the paper. Slightly above, fading streaks and marks are left behind from the bristles of his brush. These suggests his attempt to extract the remaining ink from the brush by applying force to the dry bristles, conveying immediacy, pressure, and rapid movement. A more deliberate area is where Smith applied small marks near the edges and ends of the forms, especially the cylindrical form, and aligned them with the lines of the large masses. In other words, Motherwell’s more gentle application demonstrate a harmonious relationship between the artist and medium in contrast to Smith’s more violent, dominant, and forceful relationship with the medium.

In both drawings, the use of a thin line across the paper helps define boundaries and creates the sense of expansion and compression within space. Whereas in Untitled the line marks a horizon line, in Drawing 1962 the line acts as a wall that confines the forms into a smaller space. In Untitled, the horizon line suggests there is distance beyond the forms and appears to expand back into depth. Instead of expansion, the vertical line in Drawing 1962 indicates compression as it appears to almost push and cram the forms toward the left portion of the paper. It creates tension within the curving form by suggesting a cylindrical shape on the upper portion before reverting to greater flatness through the sharp brushwork on the lower half. This reinforces a feeling of explosive energy unleashed by the bent, cylindrical form. It is as though the tension of compressed space within the cylindrical form forces it to eventually explode and project energy outward, in unexpected and almost perpendicular directions. The line therefore dramatizes the departure of the cylindrical form through a climactic build up of tension and dispersal in a jagged series of flatter brush strokes.

Another element that contributes to different temporal experiences in the two works are the inkblots that evoke the sense of weight and motion of water. In both drawings, inkblots or ink splatters make the presence of liquid materials apparent, but they operate differently in each. In Untitled, the ink blots work cohesively and collaboratively with all the forms on the paper, seeming to act as bubbles and drops of water among the translucent and cellular forms under the arrow-like arch. For instance, the ink blots under the arrow-like form are aligned diagonally, so they appear to rise and reinforce the sense of airiness of the translucent forms. More importantly, this sense of airiness contributes to the slow temporal experience as the bubbles float in a diagonal axis of movement. However, in Drawing 1962, the ink splatters work against the more rigid, geometric masses. The ink blots are much darker and organic, like blood; there is a sense of weight or seeping into the paper that contrasts with the ink washes across the surface in the primary forms. The way the ink splatters onto the paper suggests speed; the elongation of the splat is a result of air pressure and compression of the ink when flicked. The splats result from a more violent action, suggesting a sense of immediacy and possibly unease.

Negative space in contrast to the black forms also contributes to the creation of three dimensionality and the evocation of luminosity. The implied reflection of light on surfaces can convey different types of energy. The negative spaces on the translucent forms in Untitled are used to make the forms appear luminescent, which relates them to microorganisms. At the same time, the contrast of black and white evokes film negatives and microscopic views of organisms, both of which relate to the observation of movement. In evoking some of these experiences, they give energy and life to these translucent forms, creating a euphoric feeling as a result of their slow, collective ascendance. However, the opposite occurs in Drawing 1962. There, on the upper right corner, negative space runs along the lower sides of the hanging geometric-like form. The negative space suggests intense light that renders part of the form invisible, leaving only the sheer outline present. Instead of creating a translucent and lightweight form, the negative space and the equal distribution of color throughout the forms suggest metal. The suggestion of reflectivity highlights the solidness and three-dimensionality of the curving phallic form that distinguishes itself from a chaotic origin before disintegrating again toward the bottom.

In Untitled, the gap or space between the black horizontal plane and the arrow-like form suggests a form is incomplete. The lack of enclosure, along with contrast of black and green placed on top of one and another, only increase the viewer’s inclination to put the black arrow-like form and horizontal plane together to form a triangle. This suggestion of reconciliation of these visual fragments becomes an invisible force that keeps the arrow-like form grounded. It suggests that the arrow-like form is not levitating or floating in space, but rather is situated on ground. In other words, there is a sense of depth and three-dimensional space, into which the viewer is drawn. By contrast once again, in Drawing 1962, the gap or space between the cylindrical and geometric forms do not suggest reconciliation but rather separation. The dark line on the top of the geometric form creates a barrier that prevents a reintegration between the two forms. The small marks alongside the cylindrical form appear like dust particles falling after being pulled apart from one and another. The deterioration or separation of forms gives the space a three-dimensional quality that evokes the forces of gravity within the work. Negative space not only distinguishes the forms as two separate pieces but also suggests distance. The viewer’s participation seems necessary to perceive a relationship among the forms.

Robert Motherwell and Hassel W. Smith were both American Abstraction Expressionists, emerging around the same time in the mid-1900s, though Motherwell remains much better known.[1] Motherwell was not only an artist but also a writer and educator interested in both European Philosophy and American thought.[2] In one of his many writings, he writes that Abstract Expressionism arose out of a human necessity and desire to reconcile with the modern world.[3] In other words, humans were alienated and desired a sense of belonging, a place of familiarity and understanding in the world. Due to rapid urbanization in modern life, people were disoriented and unsure of their relationship to each other. Motherwell expresses concern about the “problem of choice,” in which an individual must exclude the few in favor of the many when in actuality, all are equally relevant.[4] This relates to Untitled as the drawing suggests a collectivism and collaboration between all the forms to move towards a common goal. Each form and line work together to create fluidity and energy on the paper. According to Motherwell, “drawing is the dividing of a plane surface,” in which the line speedily cuts the surface right through.[5] Drawing is movement across the surface. This relates most notably to the horizon line that cuts across the massive, arrow-like form in Untitled. Motherwell is also interested in Zen paintings, which he believes produce an emotional and spiritual experience rather than an accurate depiction of reality.[6] In his writings, Motherwell indicates that painting is a triangle made up of the self, the artistic medium, and the wider culture.[7] This can be seen symbolically in Untitled, where the arrow-like form manifests as the mark of self-presence on the paper while human culture is suggested in the translucent forms that relate to it, all conveyed through the medium of abstract paint.

Hassel Smith had traditional training in life drawing and figure painting.[8] It was not until he was exposed to the works of Clyfford Still that he decided to join the Abstract Expressionist movement.[9] More importantly, as a Marxist, he believed that art had a social responsibility to resist the materialistic culture of capitalism.[10] A friend of Smith describes his images as “an explosive attack against the materialism of capitalist society.”[11] This in part explains the immediacy of his drawing and “lightning-fast draftsmanship.”[12] The rapid, almost violent movements and the attention to the singular act in Drawing 1962 become more pointed through the understanding of Smith’s passionate political opinions. In his own words, Smith states that “[m]y paintings are intended to be additions to rather than reflections of or upon life.”[13] Rather than viewing Drawing 1962 as a simply an expression of his desire for action, the work can be understood as a declaration or call to action, as a reaction to war and political conflict in America. Perhaps Smith hoped it could have a direct impact through the arousal of viewers to take action and create change.

Dore Ashton argues that the “cultural effect of war…was to release a high-voltage charge of creative energy.”[14] World War II affected many artists tremendously in their creative process, as apparent in the work of both Motherwell and Smith. The war gave rise to a kind of necessity that Abstract Expressionism attempted to fulfill. According to Ashton, Abstract Expressionist artists during and after the war had conflicting desires, seeking a sense of belonging but at the same time liberation from everything.[15] Both drawings express a sense of belonging through the presence of community or complementary groupings of forms. In Untitled, the community migrates together while in Drawing 1962, a member of the group emerges and then separates into emancipated dispersal. At the same time, the reverse also applies, in which the suggested collision of forms generates a sense of communal interaction in Drawing 1962 while a desire for independence resides in the departure and rising of the forms in Untitled. Nonetheless, both works suggest transformation and a process of becoming. These are qualities especially suited to drawing as opposed to painting.

The works of both Motherwell and Smith convey narratives crucial to our understanding of Abstract Expressionists ideals. At the same time, the narrative of both the struggle between independence and community and the passion for transformation and change resonates widely in American culture today. These feelings still connect to our contemporary time. The artists’ expressions are felt through the temporal and sensual experiences of depth, three dimensionality, movement, pressure, and the evocation of light and water, in the works. They are created with the collaboration of line, color and negative space. The viewer is invited to participate in an emotional and exciting journey, to discover new insights into the the artist, the society, and ultimately themselves in relation to the contemporary world.

Works Cited

- Susan Landauer, The San Francisco School of Abstract Expressionism, introduction by Dore Ashton (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), xvii.

- Robert Motherwell, The Writings of Robert Motherwell, ed. Dore Ashton and Joan Banach (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2007), 159.

- Robert Motherwell and David Rosand, Robert Motherwell on paper: drawings, prints, collages (New York, NY: Harry N. Abrams, 1997), 63.

- Susan Landauer, The San Francisco School of Abstract Expressionism, 136.

- Ibid., 136.

- Ibid., 137.

- Ibid., 138.

- Ibid., 138.