Nicholas Fernacz, Lisa Gaber, Ismene Markogiannakis, and Jackeline De La Rosa

Curatorial Statement:

This exhibition explores six artists’ drawings and sculptures and how they relate to one another. While this seems like a farfetched concept, drawing and sculpture have been linked throughout art history. Often used as a preparatory vehicle, drawing has been utilized to aid artists’ thoughts in expressing a three-dimensional form. These “preliminary” works often provide unique insight into the artist’s “finished” work. Drawings, when considered finished pieces, often have attributes of sculptures, such as line, form, and shape. This exhibition displays a curated selection of both drawing-like sculptures and sculpture-like drawings. Featured in this exhibition are works, both drawing and sculpture, highlighting the abstract figure, the human figure, the abstract, and the void. Color, and the lack thereof, plays a key role visually in both the two- and three-dimensional. Included are sculptures that have a vagueness to their interpretation and completeness, much like a preliminary sketch. Some of the shading of the drawings displayed here mimic shadows as one would see with a three-dimensional form, and likewise if one were to view a sculptural piece. After viewing the works in this exhibition, the curators challenge the viewer to analyze both drawing and sculpture further, in addition to their connectedness.

Mary Ijichi, American (b. 1952)

String Drawing #2, 2002

Acrylic and string on Mylar, acrylic and metal hanger

148 x 40 in.

Gift of Werner H. and Sarah Ann Kramarsky

University Museum of Art, University of Massachusetts Amherst, UM 2003.1

Communication and language are two fundamental features of Ijichi’s artwork. She uses simple iconography to better explain the complex ways people think and communicate. String Drawing #2 is reminiscent of a hanging scroll made from Mylar which is lined with horizontally placed string coated with acrylic paint. The rows of string also contain occasional knots that may possibly represent the conflicts of communication. The piece can be looked at as if reading a book, providing a sense of continuity between each row of string or vise versa. The simplicity and strict use of line work to blur the lines between sculpture and drawing.

Henry Moore (British, 1898–1986)

Stringed Figure, 1960

Bronze, 9 ¾ x 14 1/16 x 12 in.

Mead Art Museum, Amherst College, AC 1972.55

Gift of Bertram H. Bloch, Class of 1933

Henry Moore is known for his cast bronze sculptures in organic and biomorphic shapes, often producing dramatic interactions of solid and void. His primary inspiration was the natural world, especially the integration of human form and landscape. The title Stringed Figures suggests a fusion of the two together here. The string creates a unique linear element that adds another, seemingly virtual, dimension.

Henry Moore (British, 1898–1986)

Promethée; Pandora, 1950

Lithograph, 15 ⅛ x 11 ⅛ in.

Purchase, Smith College Museum of Art, SC 1951:277-11

Taking inspiration from the natural world, Henry Moore’s lithograph drawing Promethée; Pandora includes a female figure alongside a variety of sculptural sketches of her abstract form. The irregular forms share the same textured exterior that the woman possesses. Within the forms are lighter colored, distorted forms reminiscent of the Surrealist movement spearheaded by artists such as Jean Arp, a major influence on Moore, and Salvador Dalí. These sculptural figures, while abstract, suggest the deep psychological aspects hidden within a person’s physical exterior.

Henry Moore (British, 1898–1986)

Ideas for Sculpture: Internal and External Forms, study for the sculpture Internal and External forms, four versions in bronze and wood, 1948

Brush with watercolor and gouache, black, red and blue wax crayons, black Indian ink and gray ink on smooth beige wove paper

11 ½ x 9 ½ in.

Purchase, Smith College Museum of Art, SC 1952:64

This drawing includes a drafts of different sculptural ideas shown in different colors and textures, suggesting various materials. As explained in the title, these irregular forms, interestingly color coded, suggest the internal psyche of the human mind and emotions, nestled within the external shells representing the human body. Some of these figures are are repeated in Henry Moore’s drawing Promethée; Pandora. These forms equally reflect Moore’s interest in Surrealist biomorphic abstraction.

Lee Bontecou (American, 1931 – )

Untitled, 1959

Canvas and metal

20 ½ x 20 13/16 x 7 ¼ in.

Purchased with a gift from the Chace Foundation, Incorporated, Smith College Museum of Art, SC 1960:14

Lee Bontecou’s use of line gives Untitled qualities of drawing. With highly delineated forms, stitched together, culminating into the “central core” motif often present in her work, this sculpture when viewed straight on appears to be flat lines on paper. As far as color, the black and off-white are reminiscent of classical drawings. While that is where the similarities between drawing and sculpture end in this work, Bontecou’s drawings are often studies for sculptures such as these.

Lee Bontecou (American, 1931 – )

Ninth Stone, 1965–68

Lithograph

22 x 28 in.

Purchase with Button and Rox Funds, Mount Holyoke College Art Museum, MH 1978.12.1

Lee Bontecou’s Ninth Stone, although a print, suggests the unfinished potential of drawing. This lithograph replicates some characteristics associated with the drawn sketch, such as smudges and fingerprints. These features reflect the process of hand drawing that led to the finished print. The depiction of a hole suggesting a window, and eye, or a void in space is typical of Bontecou’s work at this time and reminiscent of her 1959 sculpture Untitled, on view nearby. The blocky forms of charcoal shading and white highlights alternate to suggest multiple rings or planes of space, drawing the viewer deeper toward the central hole. The drawing powerfully evokes a three-dimensional space somehow manifesting itself through the flat sheet of paper.

Yuriko Yamaguchi (American, born Japan, 1948 – )

Origin #1, 1989

Wood, wire, and glass jars

64 x 84 x 9 ½ in.

Smith College Museum of Art, SC 1989:26

Yuriko Yamaguchi is an American sculptor born in Japan. Origin #1 contains an assemblage of 32 smaller segments, like a scientific collection. It consists of large jars with wooden elements, objects suspended in wire, curved wire strewn methodically through wooden balls, a wooden shelf, and several more abstract geometric pieces. The wall becomes the canvas for the work, suggesting a feeling of incompleteness or provisionality. The composition suggests an orchestra of objects, evoking a variety of musical possibilities from loud force to a sweet and soft melody. The piece draws directly on the wall through the arrangement of objects, recalling abstract compositions, scientific diagrams, or biological artifacts.

Barbara Hepworth (British, 1903-1975)

Project for Wood and Strings, Trezion II, 1959

Oil, gesso, pencil on board

14 ⅞ x 21 ⅛ in.

Gift of Richard S. Zeisler (Class of 1937), Mead Art Museum, Amherst College, AC 1960.1

Trezion is a place in Cornwall where Barbara Hepworth lived and worked in the 1950s. She is most famous for her wood and stone sculptures, however this work exemplifies a direct relationship between drawing and sculpture. Hepworth explores the construction and framing of space here as a complex study for a sculpture that she would produce a year later. The dynamic pattern of lines creates overlapping planes of spatial recession. Color is developed through a scratchy texture. The composition suggests a battle between internal and external voids. The tension and rotation here portrayed through the whirlpool of blue are translated by bronze forms in her sculpture. There metallic lines frame a drawing made of literal space.

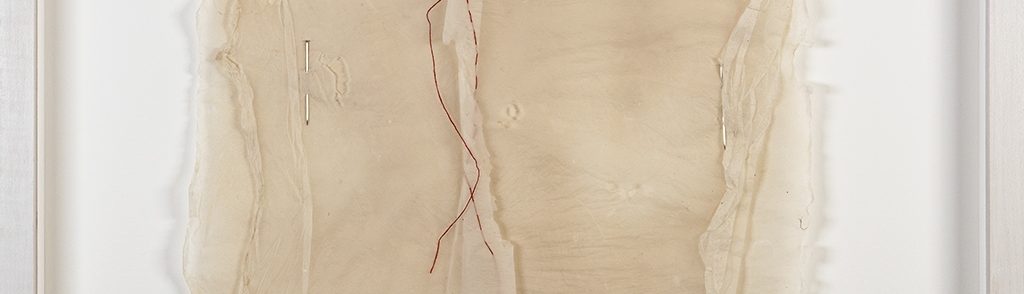

Elisa D’Arrigo (American, born 1953)

Inside Out #12, 2000-2002

Cloth, acrylic medium, acrylic paint, thread

109 x 53 x 72 in.

Gift of the artist in honor of Eleanor and Joseph D’Arrigo, Mead Art Museum, Amherst College, AC 2006.04

D’Arrigo produces a sculptural meditation on the interconnections between process and image, with no final product in mind. She creates three-dimensional forms by casting wet cloth to form linear or bowl-like shapes that can be installed in variable configurations. The spontaneity of her process directly recalls drawing. Different ways of thinking are embodied in this process of making form out of flat elements cast by hand and arranged in molecular formations. Casting creates an impression, literally and figuratively, for the viewer.