Hei Sarah,

I’m so sorry about the circumstances of your departure–that you had to leave early in the first place, and that coming back was such a rushed and harrowing experience. But I’m so glad you did share that story–it’s an important story to tell, and it reminded me of a lot of the things I’ve been taking for granted during my research experience in Norway. It’s been amazing to follow your journey to the Middle East and back, and I wish it hadn’t been cut so short. But I know you made the most of the time you had there, and it sounds like you made a lot of really meaningful connections with people in all sorts of spheres. I hope you’ll be able to keep cultivating those connections wherever you are, and that you can return to Israel/Palestine to continue the really fascinating and valuable work you started there!

Norway certainly hasn’t been unaffected by COVID-19, but we seem to have been one of the luckier countries. Most of that can be attributed to the swiftness of the response–everything was shut down before the end of February, and remained that way well into May. Even the common areas of my 5-person apartment building were deemed off-limits. The hardest part for me was the space restriction; work, sleep, exercise, eating…everything was confined to my ~25 sq. m apartment. Thanks to the swiftness and strictness of the lockdown, things have been gradually returning to the way they were when I arrived in January. Some of it was luck, some of it was geography, but the main reasons the Norwegian response could be so effective were that people still received salaries during the lockdown, there was excellent communication from the government, and the cost of healthcare is minimal. I’m very thankful that I was able to stay in Norway, but being so far away from family and friends has taken on a new level of stress during this time.

My research was actually fairly unimpeded though, despite not being able to access the department facilities. There’s always more writing to do, and once lectures began to transition to online platforms I was able to attend all kinds of talks at University of Bergen, UMass, and other schools/societies. I was even able to run an outreach program through Girls, Inc. of Holyoke with some other UMass grad students to teach kids about sediment motion in water! But I spent most of my time modeling, which I’m guessing you did as well. For anyone else reading this thinking “what’s the fashion industry got to do with geologic research?”, scientific models are representations of processes found in nature, usually on the computer or with rescaled physical components. Often, the things geologists study are too slow, too big, too deep, or too dangerous to test in a controlled experiment. Instead, we might write a model that can make predictions based on robust physical laws, see if they match observations from natural systems, and then adjust the parameters of the model. They can be really nice to watch though, like this one my labmate made to depict particles settling in still water for our outreach project.

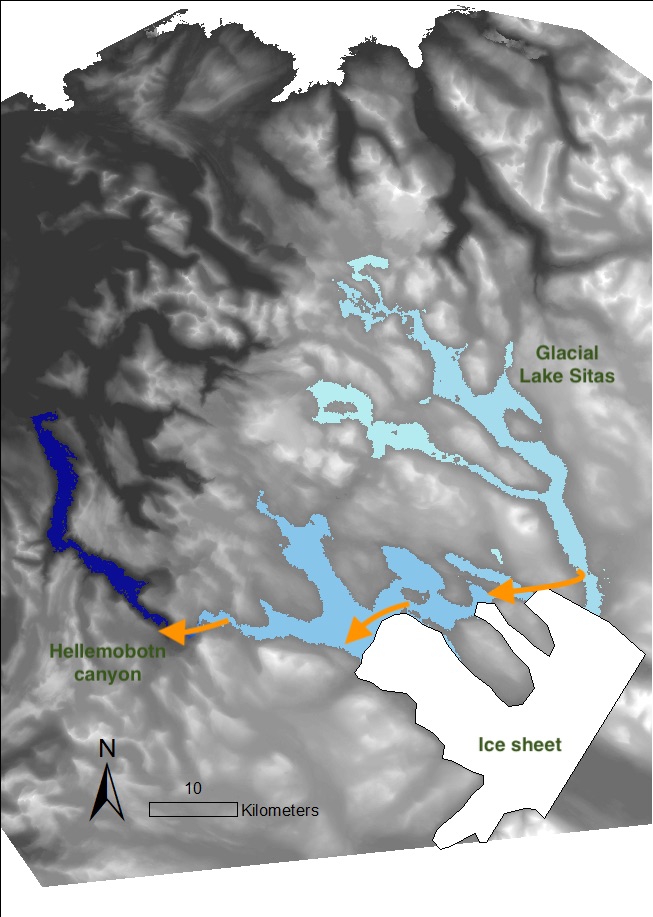

So I’ve been spending most of my days on the computer trying to model what happens when the lake I’m studying, Glacial Lake Sitas, drains. I’ve been running different versions of this scenario where the lake drains rapidly after the ice dam holding it back breaks up. I can adjust things like the position of the ice dam, the starting depth of the lake, and even the land surface to test lots of possible configurations of what actually happened there. When we go to the field (in a few days!!) we’re going to look at the spots that my model says were in the flood zone, and look for things like sediment deposits and scoured bedrock to see how closely the model reflects reality. If they match, we can use the model to calculate other things, like how fast the water was going or how much sediment can be carried by these floods. If there are big differences we might need to adjust some of our assumptions, like the position of the ice margin, and those are useful things to learn too.

Models like this make a great complement to fieldwork, since you can test things with models you’d never be able to mess with in nature, but they’re also useful in their own right. I’ve been learning and reflecting a lot over the past few months about issues of accessibility in geoscience. It’s important to acknowledge that fieldwork isn’t always safe or physically possible for everyone, and while lots of folks are working hard to try to change that, we can do a better job of appreciating the non-fieldwork aspects of geoscience too.

I’ll be in the field for the next 3 weeks, but I’ll take lots of pictures and notes to report back! In the mean time, good luck with research, and stay safe and healthy with your adorable new fluffy housemates!

Mvh,

Karin

p.s. I found a ton of mesmerizing animations of terrestrial geology models on the CSDMS website, if you’re looking for a really satisfying way to spend a few minutes!