The sad confluence of Max Roach’s death, August 16, and Warren Smith’s September 26 appearance at UMass, Amherst, afforded us a beautiful opportunity to witness the uncoiling ribbon of jazz drumming history. As the years go by, the fact that Roach earned his doctorate from UMass and taught and lived in Amherst throughout the 1970s and beyond, will become increasingly important to the cultural history of the University and the Pioneer Valley. Of all of Max’s “disciples”, Warren Smith is king. King – not only because of his age (75), and his elevated status among musicians (find me another musician whom everyone likes and admires) – but because he most fully embraces Max’s concept of the percussive arts.

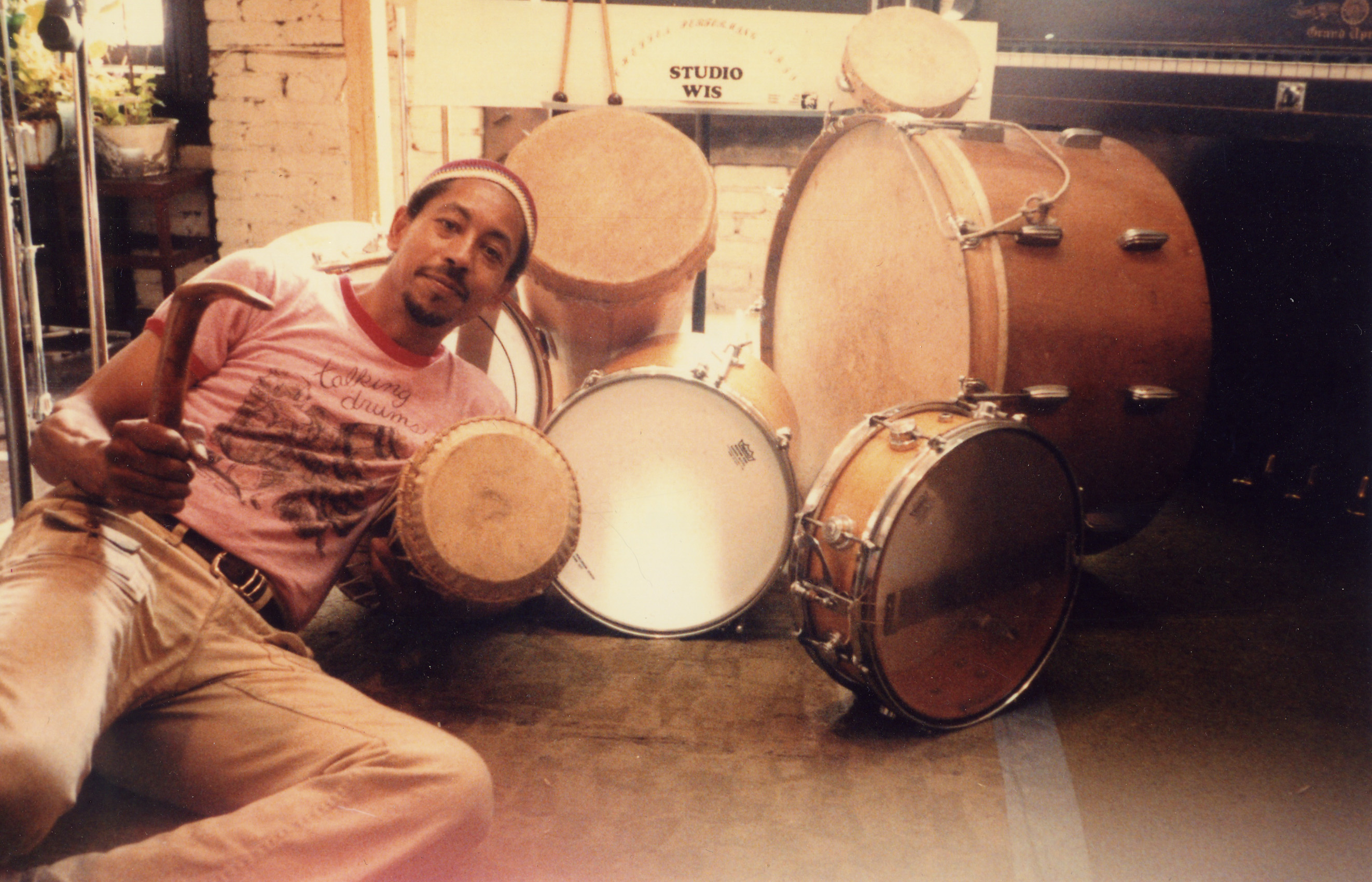

The percussive arts were front and center as Smith initiated the 6th annual FAC Solos & Duos Series at Bezanson Recital Hall before 165 enthusiastic patrons. Surrounded by marimba, three tympani, drum kit, a home-made cymbal set-up and gongs (along with an assortment of whistles and shakers), Warren moved seamlessly through two sets of moving percussion music.

Warren was a founding member of Max’s groundbreaking percussion ensemble, M’Boom, a 6-8 person group of world-class drummers who, between them, played all the percussion instruments. The respect, from an early age, that Warren had for Max permeated his entire trip to UMass. Warren began the concert by dedicating the performance to his mentor, speaking with an easy articulateness; it was easy to see his big, generous spirit. He talked about being a kid, looking up to Max. Yes, Max was playing with Bird and Dizzy. But he was also speaking up, making albums like “Freedom Now Suite”, starting his own label (Debut), lending his voice to the struggle.

Warren linked Max to Papa Jo Jones (Count Basie’s drummer), and told the story (often related by Max when he’d play his solo at the Bright Moments Festival each July), about how, after a number of drum heavyweights took the stage, saying all there was to say on the drums in honor of an ailing Gene Krupa, Papa Jo came on stage with only a high-hat cymbal and brought the house down. Warren began his Solos & Duos concert on a home-made cymbal set-up by Jackson Krall. Krall, a fabulous percussionist in his own right, takes pieces of broken cymbals and bolts them together. Strung together, the effect was electrifying. It was a highlight of the concert.

Smith shared his reverence for Roach and the history of the music for about 15 UMass Music students hours before the concert. He was “old school” in all the good ways. He talked about how to be a professional musician – be on time, be prepared musically, understand what the person hiring you wants, be sober (said with a little laugh). He talked behind a drum kit the whole time, and played it a little bit. But mostly he reminisced, answered questions and shared lessons learned over the most varied 50 year career in music history (Harry Partch, Barbara Streisand, Julius Hemphill, Gladys Knight, William Parker and years of Broadway pit band work.)

With his long time friend and helper, Anton Reid, Smith drove up from New York the night before his gig with his kit, cymbals and gongs. We supplied the tympani and marimba, which was taken apart and reassembled in Bezanson-and back again, by graduate student Ian Hale and his undergraduate minions. They did a really good deed. But then again, they got to hang with Warren for awhile. Many of them came to the show. In fact, we had an unprecedented ratio of students to general public for the performance. It’s usually around half and half; over 70% of this audience was students.

Warren also participated in a somewhat misguided (by me) experiment , the afternoon of the concert. In response to a funder’s request to get more students involved with the project, we set up shop around noon, first on the Campus Center concourse, then at Earthfoods, for a “public art display”. Warren brought part of Krall’s cymbal contraption and some great whistles and shakers. He started to play. There was some uncertainty – from artist, producer and passers by – about what it was that was happening. Within a minute of beginning on the concourse, some dude picked up a rattle and joined in. Smith, non plussed, tried to lead him along. Unfortunately he had no more skill than lots of other dudes, so the music didn’t necessarily take off. But it was cool just the same- the unpredictability of it. One problem ultimately was that he didn’t generate enough sound to captivate much public space. I had thought about asking him to bring his snare drum, but didn’t. Oh well. But I could tell the music made some friends that day, mostly because Warren was humble and good natured throughout the “event”. I think that’s why so many students showed up to the concert.

The concert was great, but for my taste, I wish he had played more drum kit and less tympani and marimba. When I asked him after the show why he didn’t let loose on the kit more, he answered that Max had already made that history and he didn’t want to merely imitate it. One high point was his “Improvision for UMass”, where he flitted from instrument to instrument, playing without pause to create a really fresh splattering of sounds and rhythm. Warren had also written “An Open Letter to the People” for the occasion. He played gongs and kit, while local poet/performance artist, Eddie Bartok-Barratta recited the words. The letter expressed his heart-felt disgust with the Bush war in Iraq, the strain it is putting on military families (including Smith’s) and the lack of funding for domestic needs because of the war. The screed was simply stated, very well read and a little long.

In its short history, the Solos & Duos Series has presented some of the most important drummers to emerge since the 60s: Sunny Murray, Rashied Ali, Milford Graves, Andrew Cyrille, Hamid Drake. Warren Smith sits rightfully among them.

Written by Glenn Siegel

Despite a coveted, tenured full professorship at UC San Diego, Mark Dresser seems always on the prowl for gigs. As he explained to me while he was in Amherst for the second Solos & Duos Series concert, he just loves to play. Although he is a committed educator and a gifted composer, he loves to perform more than anything else. Dresser inaugurated the S&D Series six years ago with a startling performance with fellow bass player Mark Helias (The Marks Brothers). That was when Dresser taught part-time across town at Hampshire College. Over the years, Dresser has suggested various duos (Denman Maroney, Patty Waters) to me, but he only had to mention trombonist Roswell Rudd as a partner, and the deal was sealed.

Despite a coveted, tenured full professorship at UC San Diego, Mark Dresser seems always on the prowl for gigs. As he explained to me while he was in Amherst for the second Solos & Duos Series concert, he just loves to play. Although he is a committed educator and a gifted composer, he loves to perform more than anything else. Dresser inaugurated the S&D Series six years ago with a startling performance with fellow bass player Mark Helias (The Marks Brothers). That was when Dresser taught part-time across town at Hampshire College. Over the years, Dresser has suggested various duos (Denman Maroney, Patty Waters) to me, but he only had to mention trombonist Roswell Rudd as a partner, and the deal was sealed.