Body Language

Over the course of art history, drawing was used mainly as a teaching tool and a preliminary step for a “finished” painting. During the 20th century, with the rise of Modernism, drawing became its own medium for artists to express themselves creatively. Drawing today links to a wide range of artistic mediums and practices, such as painting, printmaking, installation, and graphic design. Drawing is able to connect disparate topics or artistic media together, reflecting society’s increasing complexity.

For centuries, life drawing was a foundation of art, giving drawing a privileged connection to the body. Figure drawing has a unique potential to revise stereotypes and assumptions about different types of bodies, as humans are drawn to and connect with the familiarity and beauty of the human figure. This exhibition highlights the way drawings delineate bodies through tactile, visual, social, and even spiritual marks. Images of the body in the opening section of the show, “Looking,” defy stereotypes or suggest political commentary. The second section, “Touching,” presents the simple traces of bodily presence. More metaphysical statements of bodily fragility and memory appear in the final section, “Feeling.” These sometimes unexpected, often compassionate depictions of body and soul emphasize the vital importance today of recognizing our shared humanity in a divided world.

This exhibition, based on works in the collection of the University Museum of Contemporary Art at UMASS, was curated by the students in the Spring 2017 undergraduate seminar Art History 391A, “Drawing Connections: Drawing in Contemporary Art.” It is the first student-curated exhibition in the UMCA’s new Teaching Gallery. The course is taught by History of Art and Architecture Assistant Professor Karen Kurczynski.

LOOKING

(American, 1935-2009)

Reclining Nude in Studio, 1966

Charcoal on paper

Purchased with funds from the Art Acquisition Fund

Michael Mazur studied art at Amherst College and Yale University, and worked primarily as a printmaker, drawer, and painter. He drew inspiration from contemporary Italian neo-realist painters and the monotypes of Degas for his drawings, which are characterized by rich value contrasts and bold, gestural black lines. He also worked closely with other artists of his time, such as Leonard Baskin. Mazur utilizes a variety of subject matter in his work, from nude figurative portraits to plant matter to buildings. While his approach varies in content and technique, his work often revolves around themes of death, mortality, and mental illness. He alludes to these themes very subtly: some of his models rest in wheelchairs, while others lie still on beds, almost as if in a coma. These details may not be visible to the viewer upon first glance, since Mazur works to strip his subjects of surrounding context. In this work, the white, negative space of the paper works in conjunction with the dynamic lines of the composition on the drawing surface to isolate the figure. Foreshortening and facelessness make the figure appear anonymous, and even constrained, objectified, or dehumanized. The viewpoint and composition suggest an intensity if not aggression to the artist’s gaze, hidden within the drawing’s seemingly mundane content. (Eliza Young)

(American, b. 1935)

Two Figures, 1972

Charcoal on paper

Gift of the artist

Margaret Taylor depicts two nude women in intimate contact, their bodies sketched with charcoal in quick, broad strokes and broken or unfinished lines. The faces of the women are less detailed than the shapes and curves of their bodies. One woman kneels over the second, wrapping her arm around her partner’s neck and placing a hand on her thigh. The harmonious interlocking of the figures suggests a close, amorous relationship between the two women. (Victoria Fiske)

(American, 1940-2007)

Torso Drawing #19 (C4), 1977

Pencil

Purchased with funds from National Endowment for the Arts

This drawing reprises traditional figure drawing in its view of a nude female model, but in unconventional ways. The body is drawn from a stark profile angle and the value range is narrow. The artist deliberately downplays female body features. She also crops the tall, vertical figure using the horizontal paper edge, making the torso appear anonymous and asexual. At close range, representation dissolves into orderly marks that delineate abstract lights and darks. The form of the figure and the marks that make up the contours and shading present a candid and dispassionate view of the female body. (Janell Lin)

(American, b. 1924)

Models in the Studio, 1964

Pencil on paper

Philip Pearlstein is an influential American photorealist artist of the 1960s and a leading figure in the revival of figural drawings in that decade. Pearlstein strives to create paintings solely based on perception. His drawings and paintings present objective and dispassionate nude figures that do not bear any metaphorical, psychological, sexual, or other associations. Instead, they emphasize movement, tension, lighting, and space. Models in the Studio is an early drawing made at a point when Pearlstein’s mature style begins to emerge. Although the relatively loose drawing does not reflect the smooth hyperrealism of Pearlstein’s paintings, it features a similarly forthright composition and lighting. The poses might suggest a sexual interpretation given the ways that historical male artists have portrayed female bodies interacting—but the composition and drawing technique suggest a cool and indifferent gaze. He positions a horizontal model awkwardly against a vertical one, highlighting the way one model’s curved leg almost touches the other one’s head. This arrangement treats the figures as formal elements of weight and solidity distributed across the space of the image. (Janell Lin)

(American, 1916-1991)

Model on Abdomen, 1970

Charcoal and ink wash on paper

Estate of Elmer Bischoff

Elmer Bischoff’s drawing reflects his close attention to the human form in an atmospheric environment, aspects that characterize his work as a prominent Bay Area figurative painter. During the 1960’s and early ’70’s, Bischoff participated in weekly drawing sessions with fellow artists. These gatherings were both social and artistic, helping him develop the technique and composition of his drawings. Bischoff does more than simply translate the human form onto paper. Often, he situates the figure within a particular environment, so that the drawing sessions themselves become the subject. The inflection of his drawings varies from social and stimulating to moody and introspective. He tends to compose the model through generalized shapes using deep blacks and a few mid-tones, rendered with coarse textures set against the white of the paper. The drawings are loosely rendered, so that the model’s identity becomes anonymous, but they seem to capture the feeling of a specific moment in time. (Kelly Carroll)

(American, 1922-2000)

The Sheriff, 1965

Ink and wash on paper

Gift of the artist, Leonard Baskin

Leonard Baskin taught engraving and sculpture at Smith College in Northampton, MA, from 1953 to 1974. He believed that art should communicate something between artist and viewer, and that the human form and familiar imagery speak to a broader audience than abstraction. In his drawings, graphic line work and strong value contrasts create movement and drama. Baskin drew on traditions of caricature in The Sheriff, made during a time of dramatic social unrest and the struggle for Civil Rights in the South. As a Jewish man who grew up in New Jersey during the Great Depression and served in the U.S. Navy during World War II, Baskin was very conscious of social injustice. He strove to achieve morality and positive change through art. He believed that art could work to better humanity and ameliorate the problems of the 20th century. (Eliza Young)

(American, 1923-2002)

Redcoats, 1970

Lithograph, serigraph, and collage

Gift of the Century Foundation

Considered an early leader of Pop Art, Larry Rivers diverged from Abstract Expressionism and broke new ground with his expressive figurative paintings. Rivers drew on the iconic characters and dramatic compositions of history painting to discuss contemporary events. In Redcoats, Rivers uses the distinct red uniforms of the British army to conjure the American Revolution.

The impending aim of the soldiers directly threatens the viewer, despite the anonymity of their victims. The unwarranted and unjustified violence of the work had contemporary resonance with the American War in Vietnam. Even as a print, the pencil-like evidence of drawing suggests a lighthearted tone that contradicts its imposing nature. Redcoats is part of a larger series titled the Boston Massacre, created on the bicentennial of the infamous event in 1770 that left five dead. (Elizabeth Kapp)

(American, b. 1935)

A. C. Annie, 1965

Pencil

University purchase

At first glance, Mel Ramos’ works seem to merely reinforce the male gaze, the objectification and the commodification of the female body in modern society. Nude pin up girls pose with products as large as they are, or in relation to animals in compromising positions. However, in the tradition of Pop Art, another layer of meaning surfaces beyond the work’s face value. As part of his “Brand Name Beauties” series (1964-65), Ramos depicts Miss A. C. Sparkplug as a pinup girl standing next to an A.C. brand sparkplug, depicted as large as she is. She is completely nude, displaying bikini tan lines and looking straight out at the viewer with a slight smile on her face.

Like many of his pinup figures, Ramos drew this one from life, with his wife Leta as the model. In the painting based on this drawing, he adds a large AC logo behind the figure group and replaces the figure’s head with that of a smiling wavy-haired blonde. In a nod to classic academic methods of creating ideal figures using parts from different models, he presents a particularly North American 1960s beauty. Ramos’ works suggests a satirical commentary on how “sex sells” in the United States. Arguably, their juxtaposition of body and oversized product exposes the problematic use of the female body as an object of consumption in the capitalist marketplace. (Elsa Chase)

(American, b. 1935)

Peace, 1970

Lithograph, 79/100

Purchased with funds from the Fine Arts Council Grant

Peace portrays a confident woman striding forward, hands on her hips and a frank expression on her face. Repeated behind and in front of her is the word “Peace” in a hand-drawn version of a serif typeface. The letter “A” in peace is placed strategically, in the exact center of the print. The shape recalls symbolic representations of femininity as a triangular shape, and might also playfully suggest a ranking or grading of the body as a perfect “A.” Instead of relating the eroticized nude female body to commodities, here Ramos responds to the widespread protests against the Vietnam war, recalling the hippie slogan, “Make Love, Not War.” (Elsa Chase)

TOUCHING

William Anastasi (American, b. 1933)

William Anastasi (American, b. 1933)

Untitled (Subway Drawing), 2010

Pencil on paper

Werner Kramarsky Donation

William Anastasi practices abstract and conceptual art through the exploration of the multiple techniques and meanings of mark making. He uses the ingredient of chance to make spontaneous organic drawings on paper. As a native of New York City, Anastasi would often take the subway downtown to visit his good friend John Cage for daily chess matches. As the train moved, Anastasi would rest a piece of paper on his lap, meditatively hold a pencil in either hand, and let the movements of the subway guide him to create spontaneous lines on the paper. With eyes closed and noise cancelling headphones on, Anastasi became like a seismograph, and the train itself a co-author of the work. (Jessica Chien)

(American, b. 1941)

Untitled, n.d.

Ink on paper

Purchased with funds from the Fine Arts Council Grant

The early 1970s marked the decline and reevaluation of Conceptualism and Minimalism, with artists questioning whether to focus on form, idea, or subject matter in art. Joel Shapiro, who became known as a Post-Minimalist artist for his combination of simple or geometric forms with bodily references, chose to not limit himself to a single medium, form, or style. Instead, he experiments with different techniques including painting, printmaking, and sculpture. This drawing made entirely of fingerprints foregrounds repetition and spontaneous mark-making. It demonstrates his interest in process, the immediacy of making, and the passage of time. Yet, by using the fingerprint – a personal and one-of-a-kind medium – Shapiro provides an emotional and expressive quality to the repetition of marks. When Shapiro showed a similar drawing to renowned New York gallerist Paula Cooper, it paved way for many later exhibition opportunities. (Angela Yu)

(American, b. 1941)

Untitled, 2012

Gouache on paper

Gift of the artist

Joel Shapiro is an American Post-Minimalist artist best known for his figurative and geometric sculptures, which add representational content to Minimalist forms. To Shapiro, in comparison to making sculptures, drawing is liberating as it is not bound to the physical complexity and limitations of space and gravity. The use of solid black on a white background recalls his drawing and prints since the 1970s. Yet the drawing’s linear fluidity is a recent development. His loose brushwork and thick lines appear instinctive and evoke the memory of childhood. They demonstrate his long interest in using familiar forms to explore the psychological and emotional state of people. Like a Rorschach inkblot test, the lines create familiar forms that vary according to the viewer. (Angela Yu)

(American, 1939-2015)

Streetwalking, 1972

Gesso and pencil on paper

Purchased with funds from the Arts Council Grant

Rosemarie Castoro, a minimalist, conceptual artist, and dancer, created art in every medium from performance art to concrete poetry and sculpture. Her work engages the human body and its movements in multiple ways. Castoro is known for her “Y” paintings that depict choreography and human movement through abstracted forms. This drawing takes a similar inspiration, suggesting traces of two people’s movement through the city streets. Each line relates to its partner, the way two human beings might be pulled together or apart at different times. In 1972 she explicitly stated that her work “is about people and how I feel they relate to one another and myself.” (Elizabeth Upenieks)

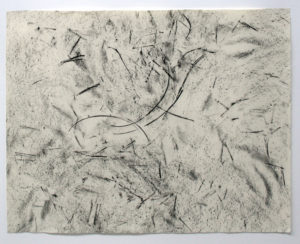

Alan Sonfist

(American, b. 1946)

Earth Mapping of New York City, 1965

Charcoal on paper

Purchased with funds from Alumni Association

Alan Sonfist is an environmentally conscious artist who translates natural processes and struggles into paper form by creating mappings of various places and environments. Earth Mapping of New York City is a charcoal rubbing of pine needles and dirt, suggesting the composition of the city long before it was inhabited. Sonfist explores the relationship of civilization with nature, or what he calls “nature culture.” Often his work dwells on human nostalgia for nature. He has recreated historical forests in city spaces through information gathered from history, science, and his own memory. “As humans, we are part of the environment,” Sonfist observes. He asks viewers to question how their existence affects the surroundings around them, and how the intervention of human civilization impacts the Earth as a whole. (Jessica Chien)

(Indian, b. 1954)

Untitled, 1986

Gouache, gesso, and pigment on paper

Purchased with funds from Alumni Association

Born in Bombay, India in 1954, Anish Kapoor studied at Hornsey College of Art and Chelsea School of Art in London, and has become a prominent name in global contemporary sculpture. Most known for his large public art projects and use of raw pigment, Kapoor calls upon imagery and forms to evoke the human body. This practice carries into his drawings, which also rely on the use of powerful colors and bodily forms. Kapoor has described his drawings as abstract expressions without any definitive intentions. At the same time, he has produced several drawings that reference feminine anatomy, suggested here by the central form which opens onto or out of a darker field. The cosmic blue color seems to downplay any anatomical reference, however, in favor of an implied space or even spirituality. The artist’s comments on the materiality of the female body as a creator, on the other hand, suggest that the rough brown texture of the surrounding field could be read as insistently physical, even scatological. (Parker Phelps)

FEELING

Spanish (b. 1948)

Build an Empire #2, n.d.

Charcoal and crayon on paper

Purchased with funds from the University of Massachusetts

Alumni Association

Francesc Torres was born in Barcelona in 1948. He left Spain in 1967 for Paris, where he experienced the labor strike and student uprising of May 1968, and has lived in the US since 1972. The title Build an Empire recalls his fascination with issues of history, memory, violence, and political power. In 1988, Torres produced one of his most well-known touring exhibitions in this gallery space at UMass, Amherst: Belchite/South Bronx. It featured concrete “ruins” that combined references to a Spanish town, Belchite, destroyed by Fascist forces during the Spanish Civil War in 1937 with burned-out walls and other artifacts of the South Bronx, then a notorious neighborhood of proliferating ruins. Torres drew parallels between life under poverty and the state of war, presenting the Bronx basketball player as a counterpart to the ordinary foot soldier in Spain.

Here, a mysterious upside-down man appears as the “shadow” of a childlike drawn figure. Torres has explained how as a child, he felt that his parents were oblivious to the politics of fascism. He was much more interested in his politically active grandfather, who had been imprisoned for 10 years by Franco. He says:

“One thing I distinctly remember from being a child is that things were a mystery. The world, the ‘adult’ world around me was always double. There was the world that was being projected towards me as a child, and there was another world that I was seeing happen. There was always this gap and my intuition was that it had to do with things that had happened before I was there.”

(Karen Kurczynski)

(American, b. 1931)

Blind Time III, 1977

Lithography

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Michael Torf

Originally from Kansas City, Missouri and later based in New York City, the American artist Robert Morris is a well-known post-minimalist and conceptual artist. He worked on several series of “Blind Time” drawings from 1973 to 2009. The drawings were made with the artist’s eyes closed but followed a strict set of guidelines. For each drawing, Morris planned a task, such as “move outward from the center making counting strokes” or “attempt to plot the entire visual field.” He estimated the time needed to carry it out, closed his eyes, covered his hands with powdered graphite or graphite mixed with oil or ink, and attempted to complete the planned task by touching the surface of the paper. These evocative drawings (and related lithographs) reveal a number of important aspects of drawing as a process, most clearly the fine texture of the charcoal and the tactility of fingers and hands encountering the paper surface. They foreground the artist’s process in carrying out a plan that, inevitably when performed with eyes closed, leads to unpredictable results. Perception, memory, unknowing, and the passage of time are some of the major themes explored in these works. (Sam Sutner)

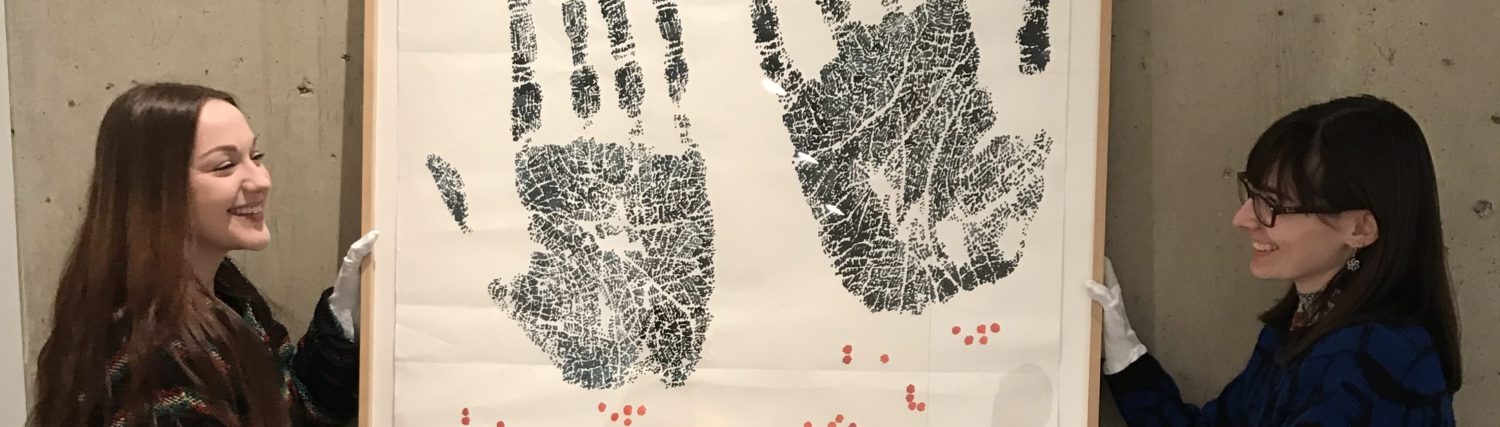

American (1939 – 2011)

Prayer, 1996

Watercolor

Gift of the artist

African-American artist Richard Yarde is best known for his large-scale watercolor paintings drawing upon themes of black heritage and family history. Yarde was born and raised in Roxbury, Massachusetts, a suburb of Boston, where he drew energy and inspiration from local dance clubs and jazz shows. Yarde was introduced to pattern making at an early age, as his mother designed and sewed dresses for a living. Yarde earned a BFA and MFA from Boston University where he began teaching immediately after graduation.

Later works such as this one became more abstract, as the artist struggled with kidney failure and strokes beginning in the late 1990s. Prayer focuses on the large black imprints of two hands (based on the artist’s own) connected by an abstract series of marks to a red, braille-like pattern. While the braille text is untranslatable, the two parts of the work suggest a body in the action of prayer. Yarde places viewers in the position of the artist viewing his own hands, but expanded in scale so that the gesture of prayer seems to extend outward. It reaches toward others, perhaps in an appeal for empathy, or a mute offering of compassion. (Joseph Mangano)